Deep Dive: History in Midsomer County

You want to take a deep dive into history of England and Midsomer County. A very good choice! Here is an overview of all the Deep Dive chapters on English history in Midsomer Murders.

You want to take a deep dive into history of England and Midsomer County. A very good choice! Here is an overview of all the Deep Dive chapters on English history in Midsomer Murders.

Each chapter begins with a synopsis to avoid spoilers if you haven’t seen all the episodes. The chapters are designed to entertain you and perhaps give you a few “aha” moments along the way.

Here you can already find here:

The chronicle of Midsomer County – sorted by year or by episode – including links to the deep dives chapters.

Coming soon:

- Midsomer Murders film locations that have played a part in Midsomer’s history – such as Morchard Manor (Loseley Park), where the famous Sayers vs. Heenan boxing match took place in 1860.

- Behind the Scenes posts about a Midsomer historian and how she works – because it’s not that different from police work in Midsomer: we’re both looking for evidence (sources) and clues (hypotheses) about something that happened in the past – and we want to know why and by whom.

- And I can think of more…

Deep Dive Chapters for English history in Midsomer County

You can use the menu to search for chapters either by season or by era.

The Fisher King in Midsomer County

The Dissolution of the Monasteries in Midsomer Murders

“Involved in the Gunpowder Plot.”

Treasures & Raiders in Midsomer County

Witch-Hunting in Midsomer County

A traitor from Midsomer in the American Independence War?

Jane Austen & Baroness Orczy in Midsomer County

The Bell Ringers from Midsomer Wellow

Sports History in Midsomer, pt. 1: Boxing

Sports History in Midsomer, pt. 2: Other Sports

Gilbert & Sullivan: Pirates of Penzance and Midsomer

Midsomer and the Battle of the Somme

•

The History of Midsomer Parva & Midsomer Worthy

The History of Midsomer Villages

Are you missing something? Do you have any wishes? Don’t hesitate to contact me.

I would like to thank Joan Street from the bottom of my heart for her work in researching and compiling the film locations and making them available to us for free on the internet -> http://midsomermurders.org. It saved me a lot of time and effort.

Dear Joan, next time we meet, some drinks of your choice are on me. 💐

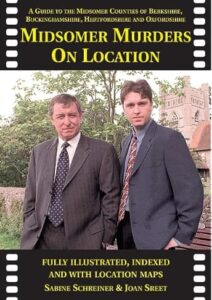

It is also available as a book, Midsomer Murder On Location, written by Sabine Schreiner and Joan Street.

•

I would like to point out that this is an unofficial fan site and I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

•

Are you here because you’re interested in English history? And don’t know about Midsomer Murders?

Midsomer Murders, a popular British television series, captivates audiences worldwide with its intriguing blend of mystery, drama and picturesque rural settings. Created by author Caroline Graham and adapted for television by Anthony Horowitz, the show first aired in 1997 and has since become a staple of British crime drama.

Set in the fictional English county of Midsomer, the series follows the investigations of Detective Chief Inspector Tom Barnaby, portrayed in the early seasons by John Nettles and later by Neil Dudgeon. Along with his various sergeants, Barnaby navigates the idyllic yet deadly villages of Midsomer, uncovering secrets and solving murders along the way.

One of the main attractions of Midsomer Murders is its richly developed cast of characters, from quirky villagers to suspects with hidden agendas. The show’s intricate plots keep viewers guessing until the very end, with each episode presenting a new mystery to unravel.

Midsomer Murders also boasts stunning cinematography, showcasing the charm of rural England through its lush landscapes and quaint villages. This visual appeal, coupled with the show’s compelling storytelling, makes for a captivating viewing experience for audiences of all ages.

For fans of crime drama and mystery, Midsomer Murders offers a compelling blend of suspense, intrigue and picturesque scenery. Whether you’re a long-time viewer or new to the show, immersing yourself in the world of Midsomer is sure to keep you on the edge of your seat as you join Barnaby and his team in unravelling the mysteries lurking beneath the surface of this seemingly peaceful county.