•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episodes: S11E05: The Magician’s Nephew)

Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutsch.

•

Tom Barnaby, wearing a black coat and a burgundy shawl, enters a church in search of Aloysius Wilmington, and discovers him kneeling in front of the communion pew in the nave, sorting. Aloysius Wilmington is also wearing a burgundy scarf, but a light grey coat over it.

When he notices Tom Barnaby, he sighs at the local rector, who doesn’t want to replace the poorly preserved Book of Common Prayer with the new ones he’s already bought for the parishes. The Book of Common Prayer is largely based on the work of William Tyndale, who was condemned as a heretic by the Anglican Church and murdered.

Tom Barnaby’s expression shows that he doesn’t know that much about Tyndale. So Aloysius Wilmington enlightens him: Tyndale is also the father of modern English prose and a forerunner of Shakespeare. But before Aloysius can delve deeper into the subject, Tom Barnaby changes the subject to the one that actually led him to him: an interrogation about the death of his magic show assistant in a kind of iron maiden.

The Englefield family

The episode was filmed at Englefield House in Berkshire, a mansion associated with the Battle of Hastings and the Domesday Book, as there was a building on the site previously owned by an Alwin. William I probably gave it to a close associate, William FitzAnsculf, or at least he owned it when the landholdings were recorded for the Domesday Book. The Englefield family is recorded from the 12th century, a Catholic family with their own chapel of St Mark as a priest’s vestry on the estate – this is where the church scene was filmed.

The Englefields were Catholic, and after Francis Englefield fled in 1559, the estate passed to the Crown. Queen Elizabeth I leased it to various favourites of the Crown and in 1635 it passed to John Paulet, Marquess of Winchester, who made his name during the Civil War. He was also a Royalist and owned not only Englefield House but also Basing House, near Basingstoke in Hampshire, which was in a strategic position.

It was besieged several times by Parliamentarians between 1643 and 1645, and John Paulet became famous for defending his house. In the end, however, it was in vain, for in October 1645 Cromwell’s supporters were able to take the house. This outcome also affected Englefield House as two thirds of Englefield House and its possessions were seized.

I will mention the small village of Englefield again in the chapter on treasure and raiders. The Anglo-Saxon victory over the Vikings – the Battle of Hallows Beck – took place in Barnaby Land …. or on New Year’s Eve 870 in Englefield.

“A book considered too dangerous to keep”

Aloysius Wilmington’s residence, just outside the centre of Causton, houses an extensive library, which is looked after by his nephew/son Simon. This collection contains many ancient books and is occasionally visited by Isolde Balliol, the self-proclaimed witch.

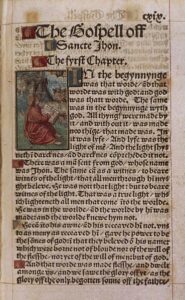

While cataloguing the books in the great library, he comes across an old book whose cover suggests a hidden content. Using a scalpel, he carefully uncovers pages written in Gothic script and discovers the title ‘The Gospell of Saynct’ and a Christian insignia. Simon realises that this is the same ‘dangerous’ book that the nameless monk mentioned, and hurries to report his discovery to Aloysius. Aloysius, like Simon, is amazed by the revelation, and both are confused by the unexpected document in the library.

He also tells Isolde Balliol that he has made an invaluable find. Isolde, who is inspired by her occultism, believes that Aloysius’s library contains the elusive Book of Thoth, a key to her longed-for magical empowerment. But contrary to Isolde’s expectations, the dreaded text is not the Book of Thoth, but a passage from a Tyndale Bible. The monk’s letter, now in a clearer context, describes the Bible as too dangerous to keep.

The Tyndale Bible

Born between 1491 and 1494, William Tyndale was educated as a theologian at Cambridge and Oxford in the 1510s. He saw Cardinal Wolsey take part in the burning of Luther’s writings in London in 1521, and King Henry VIII named “Defender of the Faith” by the Pope for (still) opposing Luther. Perhaps by this time, but certainly by 1523, he had the firm idea of translating the Bible into English and making it understandable to everyone. He asked the Bishop of London for his support, but the Bishop reluctantly refused. No, not everyone should be able to understand and interpret the Bible, only those who were educated and knew Latin. Latin was the language of scholars and the clergy.

But William Tyndale began translating anyway, and was soon considered a heretic in England. In 1523 he fled via Hamburg to Wittenberg, where six years earlier Luther had nailed his 95 theses to the door of the parish church, unwittingly starting the Reformation in Germany. Tyndale stayed here for two years and was inspired by Luther’s translation of the Bible into German and had good contact with Martin Luther. He was in close contact with Martin Luther and probably also worked with Luther’s editorial team of theologians and linguists. (Please let go of the idea that Luther or Tyndale translated the Bible all alone in a quiet, dark, cramped room. Luther’s job for his German Bible was merely to check and edit what others had translated).

Tyndale’s final chapter

Tyndale did not manage to translate the entire Bible into English – Middle English – during his lifetime, but he did manage to translate the New Testament in its entirety and parts of the Old Testament. He had the first translations printed in Cologne in 1525, but the printing of reformist texts was also banned in Germany. William Tyndale fled to Worms and had further texts printed there.

Some of it went to England, and a copy came into the possession of the monk who wrote the letter found by Simon Wilmington. Whether he only had these few leaves, or whether he wanted to keep them hidden, we do not know. Perhaps he also had leaves from his Tyndale edition hidden in other book covers.

Anyway… some time after the find, Tom Barnaby is back at Aloysius Wilmington’s for questioning, but now in his library. They sit together in the comfortable chairs – Tom Barnaby with his hands in his coat pockets and Aloysius Wilmington holding a glass of whisky.

Aloysius Wilmington empties his glass, puts it on the table, stands up, walks to the table, takes something and puts it in Tom Barnaby’s lap. It’s the found pages of the first edition of Tyndale’s New Testament from 1526. The mere possession of these pages was a sacrilege and a potential death sentence.

Sentenced to death at the stake in absentia, William Tyndale was eventually discovered in Vilvoorde near Brussels, strangled and then burned in England for safety. At the time of his death, there were still 18,000 printed copies of his New Testament alone. But only two exist – in the British Library in London and in the Public Library in New York.

No Tyndale, No Shakespeare

I got this headline from a Tyndale Society page (Tyndale.org, but the article is no longer online), and it sums up well what Aloysius Wilmington also says to Tom Barnaby in church. Tyndale invented modern English prose. And Shakespeare built on him and his neologisms, further developing the English language.

William Tyndale pioneered the modern English language with his translation of the Bible into English. Not only are the King James Version and the Book of Common Prayer largely based on his translation, but he also made the English language relevant!

Since the Battle of Hastings and the influence of the French language after the Battle of Hastings, Anglo-Saxon Old English had become Middle English and had become accepted as the common language. However, it was still not the language of the nobility and intellectuals. English was not considered suitable for imparting knowledge or for distinguishing itself from the lower social classes.

Famous word creations

Shakespeare was familiar with his namesake’s translations of the Bible because King Henry VIII broke away from the Roman Catholic Church shortly after William Tyndale’s death, and more and more English-language Bibles were printed. William Shakespeare used Tyndale’s phrases and made his inventions of words and expressions really popular. If Shakespeare is celebrated as the father of the English language, then Tyndale was something like his grandfather or mentor.

Some words Tyndale invented: “Jehovah”, “atonement”, “Passover”, “scapegoat”, “childishness”, “sorcerer”, “excommunicate”, “unbeliever”, “ungodly”.

Some phrases invented by Tyndale: “a law unto themselves”, “a moment in time”, “be not conformed to the world”, “it is done”, “judge not lest ye be judged”, “knock and it shall be opened to you”, “let there be light”, “my brother’s keeper”, “seek and ye shall find, ask and it shall be given you”, “the powers that be”, “the salt of the earth”, “the signs of the times”, “the word of God which liveth and abideth forever”.

Why “The Magician’s Nephew”?

A question that has been on my mind for a long time: Why was this episode named after one of the Narnia books? More specifically, the book that tells the prequel to The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

For those of you who don’t know the story, I’ll give you a quick summary (with spoiler, sorry!). Digory Kirke, the old uncle of the Pevensie siblings from the well-known first Narnia book, is still a boy and has met Polly Plummer in the neighbourhood. With Polly, he explores the laboratory of his uncle, Andrew Ketterley, who fancies himself a wizard.

In short, Andrew has actually created something magical and sent Polly into the Wood Between Worlds as a guinea pig. Digory follows her to save her, and they end up in another but already lifeless world, unfortunately resurrecting the overbearing, power-crazed Jadis and bringing her and them back to 1900s London. She turns Uncle Andrew’s head. And after a bit of hullabaloo, all four of them – plus cabbie Frank, his wife Helen, his horse Strawberry and a gas lamp post – end up in another parallel world. A world, which has just been brought to life by a lion with a primal scream – Narnia.

Jadis tries to seize power in Narnia, but is thwarted by Aslan and the Earthlings. Uncle Andrew, Polly and Digory return to London with an apple from Narnia, which cures Digory’s very sick mother. Later, Digory plants the seed in his garden and the tree grows and grows, until a storm destroys it. Digory, now a respected scientist, uses the wood to build a wardrobe. A very special wardrobe, as the Pevensie siblings will soon discover. The cab driver Frank and his wife Helen stay in Narnia and become royalty.

But… what does this story have to do with the episode?

I’m not quite sure.

Simply because this episode is also about misunderstood occultism, a hunger for power and a (supposed) nephew? I still can’t quite answer that, but there are two connections:

- Firstly, William Tyndale studied at Magdalen Hall (now Hertford College), where 400 years later the author of Narnia, C. S. Lewis, taught. The Bible find also fits with Narnia in general. Although the find would have been better suited to the translation of Genesis, which fits with the creation of Narnia.

- On the other hand, Ernest Balliol reminds me of Uncle Andrew. Both indulge in occultism in an unhealthy way and renounce it at the end of the story. And Isolde Balliol, on the other hand, is like Jadis. She likes to glamour, but only to achieve her goal of becoming a powerful sorceress.

Midsomer’s Tyndale is safe

Speaking of Isolde, at the end of the episode she is in Wilmington’s library and beside herself. Her father, Ernest Balliol, has told her that Aloysius Wilmington has found ~the book. Now she is angry with Simon Wilmington because she thinks the Book of Thoth has been found and he hasn’t told her. He makes her understand that the powerful book is actually the fragment of Tyndale’s Bible. Full of exuberant anger and disappointment, she snatches the papers from Simon Wilmington’s hand and throws them into the open fireplace. There, a fire is gently blazing.

Simon Wilmington rushes to the fireplace and tries to get the paper out with his bare hand. With little success. Isolde Balliol picks up the poker and, without flinching, hits Simon Wilmington over the head with it. At that moment, Tom Barnaby and Ben Jones arrive and are able to hold Isolde Balliol. Simon Wilmington can only point to the fire, groaning in pain. Tom Barnaby understands the gesture and is able to pull the leaves almost unscathed out of the fireplace.

And so there is no modern burning of Tyndale’s writings. Besides the copies and London and New York, there is now a fragment in a library in Causton. Or perhaps still in Aloysius Wilmington’s library.

Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature

- Blunt, John Henry: The annotated Book of Common Prayer. Oxford/Cambridge 1867.

- Daniell, David: No Tyndale, No Shakespeare. In: Tyndale.org. (16/05/2005).

- Ditchfield, P. H./Page, William: Parish: Englefield. In: A History of the County of Berkshire. Volume 3. London 1923. PP. 405-412.

- Ford, David Nash: Englefield House. In: Royal Berkshire History. (Not longer available.)

- NN: A hero for the Information Age. In: The Economist (December 18, 2008).

- Radnor, Naomi: The Social Universe of the English Bible. Scripture, Society, and Culture in Early Modern England. Cambridge 2010.

- Salter, H. E./Lobel, Mary D. (Eds.): Hertford College. In: A History of the County of Oxford. Volume 3: The University of Oxford. London 1954. PP. 309-319.

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 27 January 2024.

Updated on 20 January 2026.

6 thoughts on “William Tyndale”