•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episode: 13×02: The Sword of Guillaume)

Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutsch.

•

To begin with, there is a disappointment: The Sword of Guillaume mentioned in the episode is as fictitious as Sir Richard Guillaume himself. And there is no connection between the Battle of Hastings and Brighton.

I could end this article with that, but the Battle of Hastings was real, and there are small, subtle mentions and connections to Midsomer. And so there is this article.

Guillaume’s greatest butchery

We are in Lady Mathilda William’s manor in Midsomer Parva. Tom Barnaby is here because Lady Matilda, who owns most of Midsomer Parva, fired a shotgun blast through the windscreen of the Mayor of Midsomer, David Hicks, who went straight to Barnaby’s house to complain about her.

(More Midsomer Parva history? —> This way, please.)

Tom Barnaby, however, is quite gentle and dislikes David Hicks as much as she does. For Tom Barnaby has not yet forgotten and forgiven the Mayor for not only not wanting to fix his roof, but for succeeding in his corrupt machinations.

But we are not there yet, we are in Lady Mathilda’s mansion, piano music is playing in the background. The lady receives the DCI.

Tom Barnaby is about to give his gentle, mild admonition, but the lady keeps interrupting him and obviously isn’t listening. Instead, she launches into a sort of interrogation, asking him about William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings. The policeman answers correctly, but clearly hasn’t heard of Richard Guillaume. So he is enlightened:

Guillaume was William the Conqueror’s man in charge of making sure the population submitted to William, the future King of England – and anyone who didn’t was killed by Guillaume’s sword.

The sword became a symbol of English hatred of the French, especially in Brighton, where it seems many people wanted to submit to Richard Guillaume and the Normans and paid with their lives.

Richard Guillaume was the ancestor of Lady Mathilda William’s husband, as she mentions with disgust. Williams – English for Guillaume.

Relatives – an inherent evil?

As Tom Barnaby mentions in the dialogue, the Battle of Hastings took place in 1066. It was the last in a series of battles fought after the death of the childless English king Edward the Confessor. Edward had provided for his succession before his death, but only in two ways: First, he had promised his great-nephew William, Duke of Normandy, in the 1040s or 1050s, but on his deathbed he is said to have yielded to the opposition of the Anglo-Saxon nobility and appointed Harald Godwinson as his successor. Harald was the son of the very influential nobleman Godwin of Wessex.

Earlier, during his reign (1042-1066), Edward had reformed the English kingdom into a centralised Norman-style administration and filled key positions with Normans. Much to the protest of the Anglo-Saxon nobility.

The dispute was not only between Harald Godwinson and Duke William of Normandy, but also with the Norwegian king, Harald Hardråde, who was supported by Tostig. Tostig was Harald Godwinson’s brother. And while the two brothers, England and Norway respectively, fought several battles, the Norman Duke William seized the opportunity. While the other contenders were fighting at Stamford Bridge near York (not to be confused with the football stadium in London!) and Harald Godwinson was winning the decisive victory, William arrived in the south of England at Hastings. Harald marched south while William sacked the city.

A day in Hastings, 1066

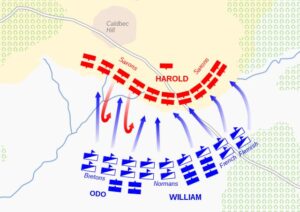

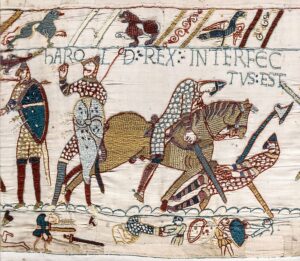

Then, on 14 October 1066, the Battle of Hastings was fought. It lasted from 9am until dark – which must have been between 5pm and 6pm – and was a bloodbath for the Anglo-Saxons in particular, and the day of Harald Godwinson’s death. The two armies were similar in numbers, as were the casualties on both sides, but the Norman army was made up of trained knights, while the Anglo-Saxon army was still a people’s army with many peasants from ancient times.

At first, however, it did not look like a Norman victory, as the Anglo-Saxon army formed a shield wall on Senlac Hill that could not be breached. Consciously or unconsciously, however, the rumour spread that William of Normandy had fallen. So the Normans retreated, and some Anglo-Saxons left the parapet and chased after them. But then came the news: William was alive! The Normans stormed back, using the holes in the Anglo-Saxon ramparts to throw them into confusion and then fought hand-to-hand for hours. By late afternoon or evening, Harald Godwinson must have been mortally wounded.

After the battle, the Normans were anything but accommodating and fair, refusing to allow the Anglo-Saxon family members to bury their loved ones. Only Harald Godwinson is said to have been buried after his widow identified him.

The Battle Abbey

The Norman dead were buried in a mass grave which has never been found. But it is thought that Battle Abbey was built over the mass grave and thus directly on the former battlefield 7 miles (11 km) north of modern Hastings, whose original Saxon settlement was moved a few miles after the battle.

William had the abbey built during his lifetime. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries it was dissolved and given to secular landowners who used the building as a residence. In 1976, with the help of some American donors, it was bought by the government and is now managed by English Heritage.

Duke William of Normandy moved north after the battle, crossing the Thames at Wallingford (Causton in Midsomer County) and then travelling along the Chiltern Hills (where many episodes of Midsomer Murders were filmed) to London. At Westminster he was crowned King of England by Ealdred on Christmas Day 1066. The new capital of the Kingdom of England became London (previously it had been Winchester).

The Battle of Hastings: A Crusade?

William of Normandy was a devout man, or at least he knew how to use the Roman Catholic Church to his advantage. William himself had the stigma of being an illegitimate child because his father, Richard II, was a polygamist and his mother was not married to him – this was not uncommon under “more danico”, Danish Viking law. The Dukes of Normandy were descended from the Scandinavian dynasty of the Rollonids, who had been Dukes of Normandy since 911. Here is the link between the Britons and the Normans: in 1002 the British Anglo-Saxon king Æthelred II married Emma, the sister of Richard II. Emma, sister of Richard II, Duke of Normandy.

When Richard II died in 1035, his son was only seven or eight years old. Edward was not yet on the English throne and was still living in Normandy. He saw the power of the underage and illegitimate king in Normandy being taken away from him. In the early 1040s, Edward became king and William was knighted. William tried to regain his lost rights – he was successful, but there was always trouble. By 1054, Edward was back in Normandy and it was probably at this time that he promised William the English throne.

Whether it was a reaction to his illegitimate birth that William was so pious and moral and interested in the welfare of the Norman Church, we do not know. But he was a champion of the Church, campaigning against simony and clerical marriage.

Before going to England, he approached the Pope and pointed out that Harald Godwinson’s commitment to the Church was lacking. The Pope gave his blessing to William’s campaign to England – almost a crusade, or at least a Christian mission.

No Sir Richard Guillaume, no sword

Guillaume and Richard were common Norman names of the time, but no Richard Guillaume can be found. There were only men in William of Normandy’s armada called either Richard or William/Guillaume.

So far I have found

- Guillaume, Comte d’Évreux (of the Rollonid dynasty, died 1118).

- Guillaume de Crépon (William FitzOsbern), seneschal of the duke, from 1067 1st Earl of Hereford, died 1071

- Guillaume de Warenne (William de Warenne), 1st Earl of Surrey, 1088 Founder of the House of Warenne, died 1088

- Guillaume Malet (William Malet), Lord of Graville, founder of the House of Malet, died c. 1071

- Richard de Bienfaite, founder of the House of Clare, died 1090

- Richard Goz, Viscount of Avranches, founder of the House of Conteville

- Guillaume de Percy (William de Percy), founder of the Percy family, died between 1096 and 1099

Sir Richard’s chapel

In the episode, Sir Richard Guillaume slaughtered the people of Brighton with a sword when they resisted the Norman takeover. He then had a church built in Brighton. Tom Barnaby meets the Reverend Giles Shawcross, who is resigned to no longer having to say mass here. While Tom Barnaby asks him about Hugh Dalgleish and Lady Mathilda, he is only interested in the historical sign on the side of the church entrance. He points to the inscription, which says that the chapel was built by Richard de Guillaume in 1069.

„Welcome to St Peter’s. Dedicated to the Seaman and Fisherman of the South Coast Throughout the Ages. St. Peter’s was originally built in 1069 by Richard Guillaume of Normanny who was given the land now known as Brightoon and Hove by William the Conqueror. The Original church was built…“.

The text on the wall of the chapel goes on a little further, but that’s all that can be read in this scene.

The aftermath of the Battle of Hastings

Yes, the Normans were far from welcome. To demonstrate and consolidate his power, the new English king, William I, expropriated most of the Anglo-Saxon nobles and replaced them with his Norman lieges. He thus established a new aristocracy in England. When he returned to Normandy for the first time in the spring of 1067 – his rule there was still not really secure – he took many of England’s most important men hostage on his first trip home to Normandy.

Before that, he changed

- the administration (centralised administration, feudal system with the Oath of Salisbury)

- the military (introduction of an army of trained vassals)

- the Church (adapting it to continental standards, replacing almost all bishops with Normans and having Norman monks found monasteries in England), and

- Trade (close links with the continent).

He also had a number of buildings built, especially castles, which were scattered around the country as a symbol of the Norman regime. To protect London from further Viking attacks and to prevent possible uprisings by the locals, he built Baynard’s Castle and Montfichet Castle near the Thames, as well as the Tower of London.

Domesday Book and the English language

The most lasting effect, however, was linguistic, as Norman French became the language of the English upper classes, judiciary and administration. The Anglo-Saxon language was relegated to a non-written language after the Battle of Hastings. Although the Norman kingship lasted only until 1154 (after which the English kingship came from the House of Anjou-Plantagenet), it took many more decades for the class and language differences to be overcome and for a common Anglo-Saxon and Norman language, Middle English, to emerge. Even today, the Norman influence can be seen in some English expressions. For example, the animal in the field is a pig, but on the table it is pork.

Not forgetting the Domesday Book, compiled in 1086, which lists for each county the landowners before and after the Conquest and their holdings, with value, tax assessment, plough, number of peasants and other data.

🤓 Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature

- Bates, David: William the Conqueror. Hew Haven 2016.

- Coad, Jonathan: Battle Abbey and Battlefield. English Heritage Guidebooks. London 2007. P. 32, 48.

- Dolderer, Winfried: Sieg der Normannen über die Angelsachsen bei Hastings (14/10/2016).

- Huscroft, Richard: The Norman Conquest. A New Introduction. New York 2009. P. 80-85.

- Medievalist Hanna Vollrath in an interview with Herwig Katzer. Cf. Katzer, Herwig: Schlacht bei Hastings. In: WDR ZeitZeichen (WDR5) (14/10/2011).

- Marren, Peter: 1066. The Battles of York, Stamford Bridge & Hastings. Barnsley 2004. P. 146.

- Williams, Ann: Æthelred the Unready. The Ill-Counselled King. London 2003. P. 42-55.

Sources

- Poitiers, William of: Gesta Guillelmi II Ducis Normannorum (1071-1077).

- Vitalis, Ordericus: Historia Ecclesiastica, Volume 4 and 5 (1110-1042).

- Bayeux Tapestry (late 11th century).

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 2 February 2024.

Updated on 22 August 2025.

The Sword Of Guillaume

Does anyone know the title of the brass band music played duriing the coach trip to Brighton?

Steve Marples