•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episodes: S11E02: Blood Wedding, and S15E01: The Dark Rider.)

Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutsch.

•

Continued from Civil War, pt. 1

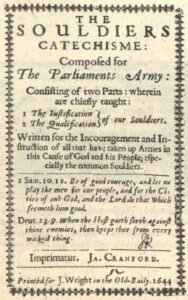

But when the Parliamentarians failed to capitalise on the successful battles of Marston Moor and Aspern Tallow, Oliver Cromwell and Thomas Fairfax formed the New Model Army – a single professional standing army of fanatical Puritans who fought not for money but for their honour, their faith and their passion.

They were very loyal, very tenacious, and very well equipped by the standards of the day.

The New Model Army was the link between the two turning points of the Parliamentarian Civil War. In 1643 the Royalists still had the most victories, but with the Battle of Marston Moor, the creation of the New Model Army, the Battle of Naseby on 14 June 1645 was a huge blow to the Royalists. At the Battle of Naseby, around 4,500 of them were captured and 1,000 died – including Geoffrey DeQuetteville from the village of Quitewell. However, as Ludo DeQuetteville explains to John Barnaby and Ben Jones, he lost his life through carelessness, clumsily sticking his head into the cannon when it was fired. Since then, a curse has been placed on Geoffrey as he rides around as a headless horseman, pointing at people – who soon die.

The historian’s delight

But it is not only Geoffrey DeQuetteville who has a bad habit, so does the family currently living there: they are re-enacting the Battle of Naseby on their land, but claiming that the Royalists won. A misrepresentation of history. Every year.

Not even Sarah Barnaby can change that, but at first she is convinced that the DeQuettevilles have an interest in making the battle as realistic as possible. As the new secretary of the Causton Historical Society, she wants to gain respect by making the Battle of Quietwell historically accurate. Her husband, who is already a good judge of the DeQuettevilles, points out that this will not be so easy – later Ben Jones will do the same – but Sarah shrugs it off, believing that this year, as in reality, the parliamentarians will win.

What she doesn’t know: Sasha Fleetwood wants to make absolutely sure that the battle is lost for the DeQuettevilles this time. Her motivation is not historical accuracy, but revenge and a bet she made with Julian DeQuetteville. And so the unsuspecting Sarah Barnaby introduce to the King’s Loyalists (“Cavaliers”) and the Parliamentarians (“Roundheads”) as they take their stand and wave their banners.

The historian’s woe

Sarah Barnaby welcomes the participants and visitors to the re-enactment and mentions that there were no battles in Midsomer County during the Civil War. (We know that’s not true because of the Battle of Aspern Tallow). She then clarifies that this time it will be a little different to the years, yes, probably decades, before, but she explains it in a little more detail for some of the participants.

One Cavalier General seems to have little patience or desire, and shouts “fire” at her monologue. Sarah Barnaby, startled, interrupts her introduction and tries to stop the inevitable, but she has no chance. The Roundheads form up and the Roundhead general gives the order to attack. Sarah Barnaby becomes increasingly desperate, regardless of the general on the battlefield in front of her.

And then the battle doesn’t go according to Sarah Barnaby’s plan at all. Instead, the Cavaliers manage to capture the Roundheads’ standard. It looks like a victory for the DeQuettevilles, but then Sasha Fleetwood’s trump card arrives: half a dozen soldiers – in today’s uniform, but with a red sash. They can regain their standard and win the Cavaliers’ standard. This is finally too much for Sarah Barnaby. She makes a snarky comment, then lets her microphone dangle from the cable over the microphone holder, causing feedback, and leaves the scene.

In the priest hole

Knebworth House in Hertfordshire was the location for Quitewell Hall. A late Gothic manor house listed on the National Heritage List since 9 June 1962. However, there was a pre-Norman manor on the site, belonging to a thane of King Edward the Confessor called Aschil. In 1086, according to the Domesday Book, it belonged to Eudo Dapifer (‘the piper’), son of the recently deceased Norman baron Hubert de Ryes. It then changed hands many times, but from 1490 it was the home of the Lytton family.

Among them was Sir William Lytton, who sat in the House of Commons as Member of Parliament for Hertfordshire from 1640 to 1648. He supported the Parliamentary cause in the Civil War, so the hidden alcove where John Barnaby and Ben Jones find the oil painting of the headless Geoffrey DeQuetteville is probably not a priest’s hole.

But there is such a secret passage at the Fitzroy’s Bledlow estate. Tom Barnaby has just arrived at the house of the latest murder victim, Robin Lawson, the Fitzroy family’s estate manager, who lives on the estate not far from the manor. Ben Jones is already there and has found Harry Fitzroy. Ben Jones wonders how he got into the house and enters the sitting room. Tom Barnaby deliberately touches the panelling of the stove. He presses a spot, it clicks and – tada! – the bookcase opens.

They go in and come out in the bedroom of the house. The room where the first victim, Marina, was stabbed through the chest and into the wood-panelled wall with an old knife.

Bledlow Manor was filmed at Joyce Grove, a manor house in Nettlebed, Oxfordshire. The Jacobean styled building was first constructed in 1900, and so has no connection with the Civil War or the period when Catholic mass was banned. It did, however, have a post-Civil War predecessor. It has been on the National Heritage List since 23 August 1999 and was most recently a branch of Sue Ryder Hospices until 2020.

Note: I’m aware that there’s another episode with priest holes, but until it’s shown on British TV, I won’t be writing more about it here.

What happened next

After the two turning points of the Civil War at Marston Moor and Naseby, the Parliamentarians won a series of other victories. First, the king repeatedly entrenched himself in Oxford. This third victory of the city lasted two months, but it was more negotiation than fighting, as the war was clearly lost for the Royalists. However, the king was able to escape to Newcastle and surrender to the Scots. From there he ordered all remaining Royalist garrisons to lay down their arms – the surrender.

A few months later, the Scots delivered King Charles I to Parliament, but Charles I was still able to persuade the Scots to come over to his side and support him again. This led to Scottish rebellions in England, but they were unsuccessful and culminated in the extradition of the English king.

In 1649 King Charles I was beheaded. The monarchy was abolished. For the first and last time, England became a republic – the Commonwealth. Puritanism became the dominant religious movement. Only in Ireland did the Catholic majority resist, which ended in a bloody massacre and the dispossession of Irish landowners.

In 1653 Oliver Cromwell staged a coup d’état against his own Commonwealth and proclaimed himself Lord Protector. For the next five years, until his death, he ruled dictatorially and absolutistically – completely paradoxical because the Civil War was not only a religious war, but also a war between absolute and parliamentary monarchy and republic.

More information

Ellis Bell was born illegitimately in Lower Warden in 1867. His mother worked on the Smythe-Webster estate and was seduced by the son of the house. Although the family denied paternity, they helped Ellis Bell get a job as a teacher. This is seen by some as an admission of guilt. Ellis Bell wrote a classic with ‘House of Satan’ and the two hamlets argue over who has the right to the work. Did he write it in Upper Warden, where his mother worked, or in Lower Warden, where he was born? Did the Smythe-Websters buy out the publishers after it was first published in 1897, burn all the books and now, 100 years later, reissue it as a sensation and film it at the same time? Now, in 2004, The House of Satan 2 is about to be made. Ellis Bell died impoverished in Causton in 1930.

Oliver Cromwell died of an illness, but it is not certain what it was. There has been speculation about poisoning, but it was probably the combination of malaria and typhoid, or malaria and kidney stones, perhaps together with sepsis.

Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature

- Bennett, Martyn: The English Civil War. A Historical Companion, Stroud 2004.

- Carpenter, Stanley D. M.: The English Civil War. Aldershot 2007.

- Chambers R. A.: A Deserted Medieval Farmstead at Sadler’s Wood, Lewknow. In: Oxoniensia 38 (1973). P. 146-169.

- Cressy, David: England on Edge. Crisis and Authority, 1640–1642. New York 2006.

- NN: Key Events of the Civil Wars. In: The Cromwell Museum.

- NN: Parishes: Knebworth. In: William Page (Ed.): A History of the County of Hertford. Volume 3. London 1912. P. 111-118.

- NN: Nettlebed. In: Simon Townley (Ed.): A History of the County of Oxford. Volume 18. Woodbridge 2016. P. 275-302.

- NN: Parishes: Watlington. In: Mary D Label (Ed.): A History of the County of Oxford. Volume 8- London 1964. P. 210-252.

- NN: Parishes: Lewknor. In: Mary D Lobel (Ed.): A History of the County of Oxford. Volume 8. London 1964. P. 98-115.

- NN: Parishes: Dorney. In: William Page (Ed.): A History of the County of Buckingham. Volume 3. London 1925. P. 221-225.

- NN: Ewelme. In: Simon Townley (Ed.): A History of the County of Oxford. Volume 18. Suffolk 2016. P. 192-234.

- NN: Ewelme. A Romantic village, its past and present, its people and its history. Here: Chapter 5: Ewelme under the Stuarts, and during the Civil War. Commonwealth and restoration.

- Rowland, Aston: Watlington Parish. In: Aston Rowant & Chilterns Spring Line Villages.

- Rowant, Aston: Battle of Chalgrove. In: Aston Rowant & Chilterns Spring Line Villages.

- Worden, Blair: The English Civil Wars 1640-1660. London 2009.

Further readings

- Civil War in Ireland: Fraser, Antonia. Cromwell, Our Chief of Men, and Cromwell: the Lord Protector. London 1973.

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 19 January 2024.

Updated on 20 January 2026.

9 thoughts on “The Civil War, pt. 2”