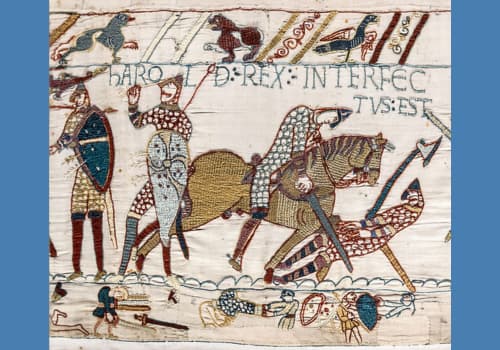

The Sword Of Guillaume

• (Caution: Contains spoilers for Episode: 13×02: The Sword of Guillaume) Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutsch. • To begin with, there is a disappointment: The Sword of Guillaume mentioned in the episode is as fictitious as Sir Richard Guillaume himself. And there is no connection between the Battle of Hastings and Brighton. I could end this article with that, but the Battle of Hastings was real, and there are small, subtle mentions and connections to Midsomer. And so there is this article.