•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episode: S13E04: The Silent Land)

Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutsch.

•

Joyce and Cully Barnaby attend a concert by a tenor singer and a pianist. While Joyce listens with enthusiasm and devotion to Ben John’s rendition of “Drink to me only with thine eyes”, Cully is visibly bored. Later, on the drive home to Causton, the two discuss the style of music, for Joyce has not had enough and listens to more singing on the car radio – much to the displeasure of Cully, who eventually falls asleep from boredom in the passenger seat as they pass the March Magna village sign.

Joyce Barnaby smiles lovingly at her daughter in the passenger seat, glancing furtively over at her. She turns down the radio. She may have looked away from the road for a second, but when she looks back, she is shocked. A pedestrian is crossing the road right in front of her. She tries to swerve out of the way, skids, and crashes into a tree at the side of the road.

Thank God, the women in the car are unharmed except for a terrible scare. But Joyce is very upset because she is sure that someone was there. She tells her husband Tom this when they go to the scene the next morning. There was no blood, so she had not run over the person.

But someone was there.

Maybe she just grazed him, and he or she dragged on a few more yards, only to die there?

Tom Barnaby’s heart goes out to him when he is called to a dead man in the old cemetery in March Magna, and Joyce, for all her grief, feels vindicated and expects the worst.

Saint Fidelis

Tom Barnaby meets his colleagues at the cemetery. After examining the crime scene, he turns to historian Ian Kent, who found the body and called the police.

Also Ben Jones, who has been looking at the gravestones in the cemetery, has a pressing question for the historian: Why are the deceased in this cemetery all so young? Because patients from the old hospital are buried here, he learns.

While Constable Gail Stephens seems well informed about the local situation, her two male colleagues have more questions for the historian. But Ian Kent seems to have little interest in discussing local history and asks the detectives to talk to his wife instead.

This is exactly what Tom Barnaby does next, finding Faith Kent alone at home. She leads him into her study and the Chief Inspector discovers three photographic prints of a large building on the wall – two exterior views and one interior view. He immediately realises that it is this old hospital, which includes the graveyard where the latest murder victim was found.

It was called St Fidelis, he learns from the local historian, and it was a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients, an incurable disease at the time – hence the many young dead in the hospital cemetery.

Film location: Fair Mile Hospital

Saint Fidelis Hospital was filmed at the Fair Mile Hospital between Moulsford and Cholsey in Oxfordshire. However, it was not a hospital for tuberculosis patients, but an institution for the in-patient treatment of people with mental illness. By 1845, every county in the United Kingdom was obliged to set one up. So this building, with its red brick, blue tile detailing and slate roof, was built in the late 1860s.

In 1870 it became the County Lunatic Asylum for Berkshire, as Cholsey was still part of that county until 1974 when it became part of Oxfordshire. The name was soon changed to Moulsford Asylum and in 1915 to Berkshire Mental Hospital. In 1948 it became part of the National Health Service and Fair Mile Hospital, which closed in 2003 due to declining use.

It later became a private school, then a visitor centre until the 1980s, when it fell into disuse and decay.

The buildings, which are substantially complete, have been on the National Heritage List since 1986 and have been used as a housing estate since 2011 (i.e. shortly after they were used as a filming location for Saint Fidelis).

Not dead but sleepeth

Tuberculosis was also known as “English consumption” in the British Isles at the time, although the then incurable disease killed a quarter of all adults across Europe in the 19th century. At the end of the 19th century, the mortality rate was still 80 per cent. More than a third of people aged 15-34 died of tuberculosis. Among 20-24 year olds, it was even half.

Among them was the woman on whose gravestone the body was found. The strange thing is: Gerald Ebbs, the murdered man – who, incidentally, was not killed by Joyce but on the spot with a piece of the grave border – was not from Midsomer County. So why was he at the grave of Caroline Maria Roberts, placing flowers there?

That’s what Ben Jones and Gail Stevens are trying to find out at Gerald Ebbs’ flat. Just then Tom Barnaby arrives and learns that the victim had collected a great deal of information about March Magna and Sutton-on-the-Hill in Derbyshire, both in the 1870s. The two places carved on the gravestone where the body was found. Was he a relative?

Gail Stephens sits at Ebbs’ laptop at the crime scene, monotonously clicking through the many photos he has recently saved there. One of the photos suddenly catches Tom Barnaby’s eye. She stops clicking and Tom Barnaby reads the bottom line of the gravestone inscription:

“‘Not dead, but sleepeth.'”

The full inscription on the gravestone reads:

SACRED

in the Memory of

CAROLINE MARIA

ROBERTS

of

SUTTON ON THE HILL

DERBYSHIRE

who passed away

June 25th 1875

in her twentieth year

NOT DEAD BUT

SLEEPETH

Tom Barnaby goes back to Faith Kent to talk about St Fidelis and is told about the suicide of a young patient in the late 18th century on a large wooden staircase in the hospital, which has since been cursed and the scene of serious accidents.

Back at Gerald Ebbs’ flat, Tom Barnaby talks to his colleagues. Ben Jones is sitting at his laptop and has just found out that there has been a suicide at Saint Fidelis Hospital. But he knows more than his boss and shows him a scanned page from an old newspaper on the laptop. At the same time, Ben has discovered the name of the woman who committed suicide: Caroline Maria Roberts. This is the woman Gerald Ebbs was so interested in.

In the scene, the newspaper report is only shown briefly, but you can read most of it:

Young Ladies Suicide.

Caroline Maria Roberts – Sutton on the Hill committed suicide by throwing herself from the staircase of The Saint Fidelis Hospital for Diseases of the chest. March Magna, Midsomer, the court heard yesterday. Unfortunately it proved to be too true.

The name of the newspaper is not mentioned.

Dust and bad air

After his first encounter with Faith Kent, Tom Barnaby sets off alone for St. Fidelis. When he arrives there, he finds himself in front of a high brick wall adorned with various tools, including a long ladder leaning against the wall. Undeterred, he climbs the ladder and peers over the wall to discover the imposing structure of the large house behind it.

He then lays a map of the hospital on the bonnet of his car. With a determined expression, he runs his finger along the winding paths on the map before turning his attention to something in particular on the adjacent wall:

There is an entrance marked on the map, but it is no longer there.

Tom goes to the spot and bends the hedge there. He finds it there – but it is bricked up and quite low. He has to bend down to get his head level with it.

Public Domain.

The Mystery of the Old Entrance

On a second visit, he asks the local historian about it. Faith Kent knows that this was the site of the old entrance, which was walled up around 1920. It was an entrance for hospital staff, who were not allowed to use the main entrance through which the patients passed for reasons of hygiene.

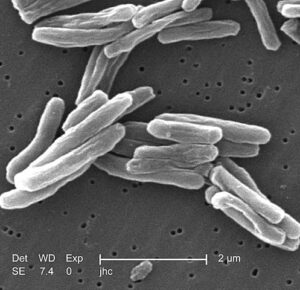

Until then, tuberculosis patients had been degraded and defamed as ‘untouchables’ because it was not really known where the disease came from and how it spread. It was thought to be spread by dust and bad air. So people ventilated, cleaned and paid a lot of attention to hygiene.

In 1869, the physician Jean Antoine Villemin showed that tuberculosis was an infectious and not a hereditary disease; thirteen years later, the epidemiologist Robert Koch discovered that the “tubercular dust” was nothing more than a bacillus; and another thirteen years later, the physicist Wilhelm Röntgen invented a device to detect and track the progress of the disease.

However, it was another half century and a year before we finally had a drug to treat and even cure tuberculosis, thanks to the development of the antibiotic streptomycin.

A romantic disease

Tuberculosis is a very insidious disease that initially has no symptoms and is not contagious. It takes weeks or even years for the disease to intensify, develop symptoms and become infectious.

The body becomes increasingly weakened by the disease, which can lead to death if left untreated. In the 19th century, the disease was mostly incurable.

Today we are amazed that in the Romantic period some people wished to have incurable tuberculosis. In fact, many artists and educated people had these thoughts, because in the Victorian era, fragility meant sexual attractiveness. The pale appearance and a weak body were something that many people were very envious of.

That is why healthy people powdered their skin as white as possible and were not afraid to use toxic substances such as arsenic to look even paler. The physical symptoms of tuberculosis and the Victorian ideal of beauty inspired and interacted with each other: beautiful were women with a narrow waist, pale skin, red cheeks and a feverish glow. (Bizarrely, sunbathing on the veranda of a sanatorium as a treatment for tuberculosis led to the development of the tan.)

A creeping disease

Classic symptoms include chest pain, night fever, cough, fever and severe weight loss – even spitting up blood. A classic treatment in the 19th century was to collapse the lung and let it heal. To make it collapse, doctors would insert air or nitrogen into the pleural cavity (the space between the lung and chest wall).

But this does not work in all cases, and in the late stages of the disease it does not work at all.

Those who could afford it spent their last weeks or years in a sanatorium. These institutions spread very quickly throughout Europe with the peak of tuberculosis in the second half of the 19th century. In the beginning, they were always at least 500 metres above sea level, because it was thought that the high altitude air could cure the heart and lungs. Later, sanatoriums were built at lower altitudes. However, the principle of airiness, of living in the air, remained the central element.

The sanatoriums were built with many balconies, verandas and terraces so that patients could do as much as possible in the fresh air, including sleeping.

Other elements were a healthy diet and light exercise. Patients who were not yet bedridden should be able to move around as individually and independently as possible. But this required separate rooms or entrances for patients and medical staff. This was because it was still believed that there was a kind of tuberculosis dust through which the disease spread.

For this reason, the corners were rounded as much as possible to prevent the accumulation of dust. And the linoleum floor and pegamoid wallpaper made it possible to clean with steam.

“It’s… nothing”

At the end of the episode, Tom and Joyce Barnaby drive home in the pouring rain. They are each in their own car, with Tom Barnaby driving. He glances at his wristwatch and when he looks back up at the road, he sees a woman wearing a wide coat over a dress with a crinoline – typical of late 19th-century fashion – walking across the road. She is walking calmly across the road, very close to his car.

Tom slams on the brakes and stops just in front of her. She doesn’t see the car and continues to walk towards the wall of Saint Fidelis. She becomes more and more transparent. Tom watches from the car as she disappears through the wall. Joyce has somehow managed to brake sharply just behind him and is still sitting in the car, watching as her completely bewildered husband gets out of the car and goes to the place where the woman disappeared.

Joyce gets out and asks if everything is all right. He does not react, but looks at the hedge on the wall and pulls the branches apart. Behind it, he can see another walled-up entrance – just like the one he discovered in another place. Exactly the same style. Joyce asks him again, now more worried. This time, Tom turns to her and you can see that he has realised that he has seen a ghost.

But of course he doesn’t show his face to Joyce and goes back to his car. Joyce also gets back into the car.

Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature

- Caldwell Smith, P.: A discussion on isolation and disinfection. With special reference to the control of epidemics. In: British Medical Journal (1889) P. 455–456.

- Clarke, Imogen: Tuberculosis, a fashionable disease? Tuberculosis has existed for thousands of years, and throughout its long history has been shrouded in myth and mystery. In: Science Museum (24/03/2019).

- Daniel, Thomas M.: Jean-Antoine Villemin and the infectious nature of tuberculosis. In: International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (2015). P. 267-268.

- McBeath, V. L.: Victorian Era Consumption. In: VL McBeath.

- Mooney, Graham: The material consumptive. Domesticating the tuberculosis patient in Edwardian England. In: Journal of Historical Geography (2013), P. 152-166.

- Mullen, Emily: How Tuberculosis shaped Victorian fashion. The deadly disease – and later efforts to control it – influenced trends for decades. In: Smithsonian Magazin (10/05/2016).

- NN: Fair Mile. In: County Asylums.

- University of Virginia: Early Research and Treatment of Tuberculosis in the 19th Century. In: The American Lung Association Crusade.

- Worboys, M.: The sanatorium treatment for consumption in Britain, 1890–1914. In: J. Pickstone (Ed.): Medical Innovations in Historical Perspective. New York, 1992. P. 47–71.

Further readings

- Wheeler, Ian: Fair Mile Hospital: A Victorian Asylum. Cheltenham 2015.

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 7 January 2024.

Updated on 15 June 2025.

6 thoughts on “Not Dead But Sleepeth”