•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episodes S13E05: Master Class, and a bit for S14E06: The Night of the Stag)

Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutsch.

•

The Fieldings’ manor, Devington Hall, is currently hosting auditions for Sir Michael Fielding’s Master Class. The manor is a 19th century country house, the grounds of which belonged to the Knights Templars several centuries earlier and has been built on since at least the 14th century. Its real name is St Katharine’s Convent and it is situated in the little hamlet of Parmoor, Buckinghamshire. A very detailed documentation of the house, which has been on the National Heritage List since 22 January 1986, can be found on the Buckinghamshire Gardens trust site.

Tom Barnaby is sitting in the last row of the Fieldings’ concert hall, with whom he had come into contact shortly before. A young woman, Zoë Stock, had reported that a blonde woman of about the same age had drowned in the nearby river. After a thorough search, no body was found, but the case continues to haunt the DCI. Unlike Zoë, he knows that about 20 years earlier a woman of her age actually drowned here.

And so it’s no surprise that he doesn’t sit still, but improves the shining hour and does some snooping around the manor.

Almost unnoticed, he makes it out of the room towards the end of Orlando’s Guest audition. Only Francesca Sharpe’s father notices him, but is still irritated by Francesca’s announcement that he should leave her alone and doesn’t wonder about Tom for more than a second.

Tom Barnaby takes the first room on the right as his first port of call and ends up in the library. With his hands in his suit pockets and an interested, sniffing expression, he takes a few steps into the room and looks around.

Tom’s discovery in the library

Meanwhile, Francesca Sharpe is now having her audition in the concert hall, Joyce Barnaby notices that her husband is no longer in his seat. She works as a volunteer for the Fieldings and helps to organise the auditions. Annoyed, she goes in search of her husband and also leaves the hall. He is still in the library. Does he want to miss the performance of wunderkind Zoë Stock’s? Oh, no, of course not!

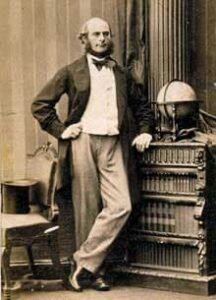

He is about to leave the library when his gaze lingers on a small portrait framed in dark wood. He bends his upper body forward to see better. It is a photograph on a red-painted passepartout and shows a man with a whisker standing frontally in a room with a commode and lamp. His left leg is placed in front of his right and he is holding onto the dresser with his left hand. it is in sepia colours.

Joyce has noticed that Tom is not following her and asks what’s going on. Tom points to the photo and recognises Sir Francis Galton. Joyce has never heard him, while Tom is thrilled. Francis Galton! The man who discovered that every human being has an individual fingerprint. He revolutionised police work.

Joyce is not quite so enthusiastic about Galton, and doesn’t want to be late for Zoë Stock’s audition. She urges Tom again to come to the concert hall, which Tom finally does. But not without thinking about why a pianist has a photo of Francis Galton hanging on the wall of his library.

The all-measuring man?

Now it is not really the case that it has only been known for a good 150 years that every human being has differently pronounced skin ridges. Think of the method of palmistry – it was already known in the early advanced civilisations, for example Babylonia, Assyria or in ancient Egypt.

Sir William James Herschel was the first to use it to identify people. He was the Secretary of the Board of Revenue of the British Raj, the civil service in the British colony in India. Building on this, Dr Henry Faulds was the first to propose its potential use in forensic work in 1880. Both were the first to propose the introduction of fingerprints to identify criminals.

However, it was Francis Galton who was commissioned by the British colonial government in the British Raj in 1888 to develop an uncomplicated personal recognition system – wrote Galton. I don’t yet know whether this is really true. I am sceptical because Galton is not supposed to have mentioned at all that the idea and the first research on this did not come from him, but Herschel and Faulds. Nevertheless, Galton published three books between 1892 and 1895 on this subject: Finger Prints (1892), Decipherment of Blurred Finger Prints (1893), and Fingerprint Directories (1895).

But we have now read so much Galton’s name, who was he anyway?

Mostly yes

Oh, that’s not so quick to answer because Francis Galton was very inquisitive and wanted to explore everything possible himself – a bit like his 13-year older cousin Charles Darwin. He simply measured everything that could be measured and is listed as a

- Naturalist

- Writer

- Geographer

- African explorer/tropical explorer

- Meteorologist

- Polymath

- Statistician

- Sociologist

- Psychologist

- Anthropologist

- Inventor (for example, the Galton whistle, instrument for generating extremely high tones in the ultrasonic range), and a

- Psychometrician.

Quite a lot.

Galton’s education

Initially on a medical career path, Francis Galton, urged by Charles Darwin, paused his medical studies for rigorous mathematical training at Cambridge. Both being affluent, the Darwin and Galton families had the luxury of not depending on employment for a living. Charles, recognizing that the medical field wasn’t suitable for Galton, encouraged him to pursue his own course.

Embarking on an expedition to unexplored African territories from 1850 to 1852, Galton authored “Art of Travel” in 1855—a practical guide for bush exploration. This expedition, coupled with the biases evident in his findings, influenced by Darwin’s “Origin of Species” (1859), shifted Galton’s life trajectory.

Galton, now convinced of the heritability of talent and character, examined the family backgrounds of judges, military leaders, and lord chancellors. Discovering that their sons often followed similar paths as more distant relatives, he dismissed objections about eminent fathers facilitating opportunities for their sons. Nicholas Gilliam, in “Cousins: Charles Darwin, Sir Francis Galton, and the Birth of Eugenics,” noted Galton’s refusal to fully consider the role of environment.

Despite prevailing views of his time, Galton faced skepticism and rejection during his lifetime. His bias-driven experiments aimed to legitimize his hypotheses rather than aligning with common sense in Victorian-period science. Galton’s pursuits reflected a determined individual trying to substantiate his own ideas, challenging the norms of his era.

More than a fingerprint man

Apparently Joyce Barnaby finds the man on the wall in Devington Hall not so uninteresting after all because a little later she is reading a biography of Sir Francis Galton in bed. The clock on Tom Barnaby’s bedside table shows half past ten. Tom comes out of the bathroom in dark blue pyjamas with a white towel in his hand. He switches off the bathroom light and asks what book Joyce is reading. At first he is delighted that she is now also interested in Galton. But Joyce already knows more than her husband. Tom Barnaby looks incredulous when she mentions with a critical eye that Galton’s biggest fans were the Nazis.

The DCI now wants to know more about this. Joyce hands him the book, wishing him good night. As she switches off her lamp, Tom flips the book, reading avidly all night.

A disgusting man

The next day, Tom Barnaby also knew that Francis Galton’s only interest was genetics. Galton, however, did not use the term genetics, but introduced “eugnics” as a new term in English science in 1883, borrowed from the Greek word “eugenes”, which actually means nothing other than “well-born”, but was used by him in the sense of “good inheritance”. Here, his two-part paper “Hereditary Talent and Character”, published in “Macmillan’s Magazine” in 1865, should be mentioned in particular.

Galton’s disgusting notion asserts that intelligence and personality are largely hereditary, suggesting specific measures to enhance the English population.He was desperate to find personal and psychological identification elements to support his hypotheses. He was by no means objective.

The certain measures were, for example, a ban on the reproduction of people who were not talented. Galton also described this very clearly in his novel Kantsaywhere („Can’t say where“), which he finished in 1910, shortly before his death.

The novel describes his notion of a eugenic utopia: The Eugenics College of Kantsaywhere determine the fate of its people based on a test. Those who fail were segregated into labour colonies where having children was a crime, others were encouraged to emigrate. Those who pass the test pass it with an equivalent of a degree or with honors.

The ideal age

In Kantsaywhere, Galton sets the ideal age to form a reproductive alliance at 22. Why 22? Well, according to Galton, this allows the production of four generations of superior people per century, provided they all pass the test.

And the same was probably on Sir Michael Fielding’s mind when he impregnated his daughter Molly. Apparently, despite her medication, she was potentially on the side of those who passed the Kantsaywhere talent test.

About 21 years later he wants to impregnate his daughter Zoë and that she has talent, well, no test is needed. We know Zoë’s age at least from the picture in Jonas Slee’s bar: Molly was still alive in autumn 1990 and we are now in autumn 2010.

Tom Barnaby notices Zoë looking rooted that framed photo on the wall with Molly.

The picture is shown in close-up. There are eight people in it, six men, two women. It was taken in front of this building. They are all estimated to be between 20 and 50 years old. They are all smiling or laughing when the photo is taken, only the woman Zoë is referring to is looking melancholy. At the bottom of the photo is a small note with the date “Autumn 1990”.

As the DCI was investigating the case at the time, he knows it’s Molly. But how can Zoë know? She was an infant at the time? Well, we later learn that Molly is Zoë’s biological mother and that she witnessed the scene under a bush.

The Stag and the Queen Bee

Almost exactly a year after the events of Fielding’s Kantsaywhere, John Barnaby, nephew of Tom Barnaby, engages in a peculiar conversation with his wife Sarah in their kitchen. Initially, the discourse involves John and the family dog, Sykes, revolving around a honey loaf. The queen bee’s strategy: a thin maiden flight to maximize distance and mate with drones from other hives.

While Sarah sits amidst papers with her laptop and a glass of red wine, she interjects, mentioning that locals also adopt similar practices. Intrigued, John is perplexed, prompting Sarah to clarify. Rising from her seat, she approaches John by the toaster, taking a nearly empty wine glass and a bottle to refill it. She enlightens him about the historical prevalence of incest risk in highly rural areas. Small villages with limited opportunities for mobility and few newcomers created conditions conducive to inbreeding. Economic hardship forced many to migrate to urban areas, diminishing the population and exacerbating the risk.

In hamlets, a tradition formed: men, on a designated day, moved between locations to mate with women from different areas, Sarah explains. This tradition, she reveals, is the root of customs like Stag Night and rutting fights.

Why some old traditions should remain forgotten

John Barnaby’s expression becomes very thoughtful. Sarah is irritated by John’s petrified expression, but he just understands the context of the Stag Night cult in Midsomer Abbas and Midsomer Herne and also why Peter Slim had to die. To verify his assumption, he asks Sarah what day that one day of the year was. And is confirmed: It’s Beltane. (Note: It should actually be 1 May because the stag cult is connected with Beltane).

The connection between Midsomer Abbas and Midsomer Herne by the Frost in 1370 was not the only one that existed. For decades, centuries, the men of the two villages went across the valley to the other village to mate in order to avoid the risks and consequences of incest. However, this should be a tradition among the local villagers. Not a new arrival like Peter Slim.

This tradition that had not been practised for 60 years (i.e. since around 1951). Thank goodness, one has to say, but the two village leaders, among others, see it differently and want to revive the tradition so that it does not perish and fall completely into oblivion.

It is possible that this tradition already existed in 1370. And is the reason why Midsomer Herne naturally helped out the starving inhabitants of Midsomer Abbas.

Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature

- Bulmer, Michael: Francis Galton: Pioneer of Heredity and Biometry. Baltimore 2003.

- Gilliam, Nicholas: Cousins. Charles Darwin, Sir Francis Galton and the birth of eugenics. In: data mine (2019). P. 132-135.

- Kritische Psychologie Marburg: Sir Francis Galton. Begründer der Differenziellen Psychologie, Begründet der Eugenik. In: Kritische Psychologie (2007).

- NN: Francis Galton, about 1865. In: DNA Learning Center.

- NN: A Brief History of the House. In: St Katherine’s Parmoor.

- The Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust Research & Recording Project: St Katherine’s, Parmoor. In: Understanding Historic Parks and Gardens in Buckinghamshire (December 2014).

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 28 December 2023.

Updated on 20 January 2026.

6 thoughts on “Francis Galton, founder of eugenics”