•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episode: S13E06: The Noble Art)

Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutsch.

•

Cricket is played in many episodes – even actively by Sergeants Gavin Troy and Ben Jones – but unfortunately the history of cricket is never discussed, and football is completely absent. However, there are mentions of historical events in three other sports, each involving very successful Midsomer County sportsmen: chess, Formula 1 and boxing. See: Sports History in Midsomer, pt. 2.

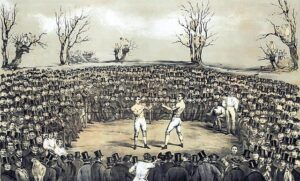

Boxing is the subject of this article. And we begin – how could we not in Midsomer – with a re-enactment of the famous boxing match between Tom Sayers of England and John Heenan of the USA on the grounds of Midsomer Morchard.

Not even Tom Barnaby knew that this famous bare-knuckle fight took place here, here outside of Morchard Manor. Queen Victoria was not present, although she would have been interested, but the famous authors Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray were.

Illegal but aristocratic patronage

This suggests that Midsomer Morchard is on the border of another county, as it was common in those days to hold the illegal prize-fights close to the border. This allowed spectators to cross the border quickly and escape the threat of jurisdiction.

But how did this fascination with a sport that was not even legal, but classified as an affray, an assault and a riot, come about? Pugilism became socially acceptable around 1700. From 1698 there were pugilistic contests which, despite their illegality, took place in London’s Royal Theatre. One of the prizefighters, James Figg, attracted so much attention and enthusiasm that he was crowned champion of England and remained so for 15 years (1719-1734).

Jack Broughton was one of Figg’s pupils and is credited with laying the foundations for boxing to become an accepted and respected sport: He set the first rules (1743) and enjoyed aristocratic patronage. This may have something to do with the fact that by the 1800s it had become unfashionable to carry swords and other deadly weapons used in duels.

In any case, the English aristocracy’s interest in and patronage of prizefighters increased when the lightweight Daniel Mendoza thrilled and fascinated them with his style of fighting – speed rather than strength.

The peculiarity of Broughton’s rules was that the fight was divided into rounds, with half a minute’s rest between rounds. The rules also provided for a referee.

This added a degree of order and fairness to the fight, which continued to be fought without gloves, without weight divisions and without a maximum duration. Also, under Broughton’s rules, it was still permitted to wrestle and punch an opponent after throwing or hitting him on the canvas.

Wrestling allowed

Regency England was the height of British boxing. The aristocracy loved the sport more and more and although it was still illegal, police raids were no longer carried out with the utmost severity, but very laxly. In fact, even the King, George IV, was a great supporter of boxing and asked some famous prizefighters to act as his bodyguards at his coronation.

In 1838, 17 years after his coronation, a new set of rules was introduced, the revised 1853 version of which was still in force at the time of the Sayers-Heenan fight:

The London Prize Ring Rules were a set of 29 rules initiated by the British Pugilists’ Protective Association. After the Broughton Rules and Daniel Mendoza’s fighting style, they were another cornerstone of boxing’s move towards legality.

Wrestling was still allowed, as were spiked shoes (within limits) and holding and throwing an opponent. They were still bare-knuckle fights, i.e. without the use of gloves.

Limited brutality

New was the size of the boxing ring, 24 feet or 7.32 metres square, bounded by two ropes. And although wrestling and spiked shoes were still allowed, the new rules limited the brutality somewhat. Fouls included kicking, gouging, head butting, biting, low blows, scratching, hitting while the opponent was down, holding the ropes and using resins, stones or hard objects.

The fight had several rounds, but there was no maximum number of rounds or duration. It lasted until one of the opponents could no longer fight. That is, if he could not get to the scratch, the starting position at a marker in the centre of the ring, within 38 seconds without help.

No points were awarded, but the fighters could agree to a draw with the referee. Other possible reasons for a stoppage were crowd disturbances, police interference, harassment or simply because night had fallen and nothing could be seen.

42 Rounds

The fight between Brighton’s Tom Sayers and the American John Heenan was regarded as the first world championship in boxing and attracted a level of publicity that boxing in England had never seen before. The New York Times of 31 March 1860 reported that several members of Parliament were among the spectators, as well as the aristocracy and many of London’s literary, artistic and sporting celebrities. Transport from London was provided by the North Western Railways. And yet boxing was illegal.

It is true, by the way, that the writers Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackereray were among the spectators, as Farquaharson mentions. So were the then Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, and the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII.

The match started at 7.30am on 17 April 1860 and lasted two hours and 10 minutes. Sayers was the favourite, having won twelve out of fifteen bouts. Heenan, on the other hand, was celebrated in the USA as a successful, powerful boxer, but he had only fought in two prizefights – and lost both. Everything looked relatively straightforward, but Heenan managed to knock his opponent down in the third and fourth rounds, perhaps because Sayers was facing the sun. Then, in the sixth, Sayers’ right arm was so badly injured that he had to fight with one hand for over an hour. In the seventh round he managed to punch Heenan several times in the eye, which then swelled up.

An abrupt end

Then, in the 37th round, Heenan pushed Sayers’ neck against the top rope, almost illegally choking him. The ropes were then lowered to save Sayers’ life. Normally, when the ropes came down, the fight was over and the crowd poured in. There was a hell of a pandemonium – well, not unusual for Midsomer County, was it?

Anyway, the referee wanted to stop the fight and declare it a draw, but the opponents were having none of it. So the ring was moved a few yards to the side and the fight continued.

However, in the 42nd round, the fight was stopped when police were spotted on the sidelines and the fight was declared a draw. Both fighters were awarded championship belts. Sayers never fought again.

The Noble Art…

“As soon as the Englishman had brought the use of his fists to a ‘science’ – or, perhaps, as he preferred to call it, to ‘the noble art of self-defense’ – he began to look upon the use of the knife as cowardly, as a practice utterly beneath his contempt. And so it came to pass in due time that among foreign nationalities the fists of the ready Englishman were always more to be dreaded than the murderous knife of the desperado.” (Source: Frederick W. Hackwood: Old English Sports. London 1907. P. 198-199.)

This was not the end of the story, however, as controversy and animosity continued for weeks. The British saw Sayers in the lead, the US raged that Heenan was ahead. Deliberately tipped off about the location of the fight, the police ensured it would be stopped, robbing Heenan of his victory.

Iain Manson investigated both the newspaper reports and the controversy a few years ago and concluded that Heenan was probably very close to winning.

The re-enactment at Morchard Manor was to be a different story: Not only did Queen Victoria – portrayed by Joyce Barnaby – attend the battle and unveil Libby Morris’ Sayers sculpture.

No, newly crowned world champion John Kinsella was to play Sayers, and Justice of the Peace Farquaharson’s son Sebastian was to play John Heenan. And, of course, the plan was for Kinsella to win as Sayers.

… but make it more midsomer-esque

In fact, the re-enactment ended with a mix-up, with Ken Tuohy standing in front of Kinsella instead of Sebastian. He is the sculptor’s husband and she is cheating on him with John Kinsella. Yes, a typical Midsomer-ish mess and probably this fight would have been pro Tuohy-Heenan had Gerald Farquaharson not intervened.

Yes, the battle between Sayers and Heenan did take place, but not in Midsomer County, but in a field near Farnborough in north-east Hampshire and the Surrey border – and 10 miles / 16 km from the filming location: Loseley House, mentioned in the Domesday Book as “loosely” held by Torald. The present building is also of Elizabethan date and has been little altered externally since its construction in the 1560s. Stones from Waverley Abbey, which fell into ruin after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, were used in its construction – and it was itself a recurring film set for Midsomer Murders episodes, for example St Frideswide Abbey, but also as the abandoned monastery of Monks Barton.

Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature

- Hackwood, Frederick W.: Old English Sports. London 1907.

- Manson, Iain. The Lion and the Eagle. Cheltenham 2008.

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 8 February 2024.

Updated on 20 January 2026.

7 thoughts on “Sports History in Midsomer, pt. 1: Boxing”