As well as playing a lot of cricket, Midsomer has been very successful in chess, Formula 1 and boxing. The famous boxing match of 1860 is a topic for another time: here we look at chess and F1 first.

•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episodes: S06E01: A Talent of Life, S08E02: Dead in the Water, S14E01: Death in the slow lane, S15E05: The Sicilian Defence, and a little bit of S05E03: Ring Out Your Dead and S19E03: Last Man Out)

Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutsch.

•

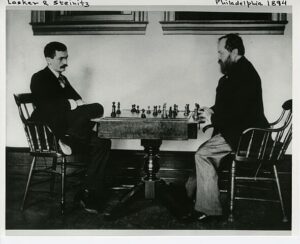

In 1893 there was a world champion from Bishopwood in Midsomer County: Reverend Stannington.

John Barnaby learns this in passing during an interrogation of the descendants of Edward Stannington after he was murdered by a lake. He questions Edward’s aunt Vivian and learns that one of her ancestors, the Reverend Stannington, was the 1893-1894 World Chess Champion. What Vivian Stannington fails to mention is that her ancestor died in 1894, so was unable to enjoy his world championship.

The location for the Stannington house is the manor house in Warborough, Oxfordshire. Here, in Warborough, there was a settlement as far back as Roman times, and it is listed in the Domesday Book as part of the extensive royal estate of Benson. The manor house, formerly known as Beech House, was built in the late 17th century but has been altered several times since. It has been on the National Heritage List since 18 July 1963.

World Chess Champion 1893-1894

The game of chess probably originally came from the Indo-Pakistani-Arab region to southern Europe and then to Britain – probably as early as the Norman period. But it was not until the early 19th century that chess clubs, chess tournaments, chess books and chess magazines began to appear. The first world chess championship was held in 1886. It was won by Wilhelm Steinitz against Johannes Zuktort – and Steinitz remained world champion until his match against Stannington. The games took place in the spring at three different venues in North America. And the world champion was the first to win ten games – and this time it was not Wilhelm Steinitz.

It was not all that surprising, as quotes from the run-up to the World Chess Championship show.

“ Ask me something easier. I know only on thing, that Steinitz never in his life met a man of Lasker’s strength.” the US chess player Jackson Whipps Showalter is quoted in the New York Times and his compatriot and also chess player Eugene Delmar in the same place: “Lasker’s youth might help him along, but Steinitz is Steinitz after all. Nay, I can’t commit myself to name the winner.”

Oh yes, Lasker, that was more or less Reverend Stannington’s real-life alter ego, who actually won the World Championship, which incidentally was not played until 1894. And unlike Reverend Stannington, Emanuel Lasker did not die shortly afterwards, but remained World Chess Champion for another 27 years and lived for another twenty years after that.

„While I have not played serious chess since my match with Tschigorin, I have had no end of domestic trouble and bother during the last two years.” Wilhelm Steinitz is quoted as saying in the New York Times. “Still, I am confident that I can play chess as heretofore. I never underrate an opponent, and I believe that Lasker is a really fine player. Moreover, the latter had the chance to study all my games, my book, and therefore my style, and if I do lose he will have to beat me with my own weapons.”

Knight2King

Alan Robson, chess player, online game developer and father of the missing Finn. He is being questioned by John Barnaby and Ben Jones at the CID in Causton. As he is about to leave, his gaze falls on Barnaby and Jones’ area of the CID’s open-plan office. Specifically, a number of A4 sheets of paper taped to a cupboard. Oh, how well he knows!

The three men are standing in the area of our two investigators. Ben is watching with his arms crossed, slightly in the background of the scene, leaning against a desk. John is standing by the cabinet with the printouts and Alan Robson is writing these moves on a plexiglass wall – by heart. He pauses to explain why he knows these moves so well.

These are the chess moves that an internet user nicknamed Silverfish used to beat the reigning world chess champion Vladimir Kostelov a few years ago.

A World Chess Champion

At the heart of the episode is a chess game that has existed before: Kasparov Versus the World, played in 1999 between the reigning world chess champion Garry Kasparov and internet users.

Kasparov’s success was due in part to his unrivalled knowledge of chess opening theory, i.e. how do you start a game? How do you position your pieces in the first move or two so that you can checkmate your opponent as much as possible fifty or a hundred moves later? One variation Kasparov chose was the Sicilian Defence, which was first documented in 1594 in – wonder of wonders – Sicily. It is Black’s response to White’s move from e2 to e4.

White: pawn from e2 to e4.

Black: pawn from c7 to c5. This one move is the Sicilian Defence.

That’s it.

The advantage of this variation is that there is no feeling out, but it leads directly to a sharp fight – and can quickly lead an experienced black player to victory.

This variation was very popular for a couple of centuries, but fell out of favour in the course of the 19th century. Wilhelm Steinitz, for example, did not like the Sicilian Defence.

Online Chess

There is no mention of when the online game – apparently a competition with several single games in a knockout system – took place. It is only mentioned that Vladimir Kostelov, like Kasparov, was a world chess champion in the 1980s and was bought in for this online game for a fortune.

Perhaps Kostelov saw the opportunity for self-marketing via the internet – a pioneer of personal branding via new media, so to speak. It was the same with Garry Kasparov, who from the end of the 1980s played several competitions under tournament conditions against some chess programs – and won almost every game.

Then, in 1999, he went one step further with an even newer medium: the Internet. “Kasparov Versus the World was a media-rich event that took place on the MSN Gaming Zone between 21 June 1999 and 22 October 1999 and attracted over 50,000 people from more than 75 nations – and that was just for one game.

Against the chess world

The “Kasparov Versus the World” media spectacle was open to anyone registered in the MSN Gaming Zone. Microsoft also provided a bulletin board forum for discussion in the Gaming Zone, and the ingenious system worked as follows:

First, Kasparov had 12 hours to make his move. Then four young chess geniuses also had 12 hours to watch it and – each for themselves – write a recommendation. These recommendations were posted on the MSN forum, discussed and then the possible moves were voted on. The move with the most votes after 18 hours was validated for another 6 hours and then drawn.

So it was not a multi-stage knockout system with several games, but a single game.

The four advisers to the World Team were 16-year-old Étienne Bacrot, 19-year-old Florin Flelecan, 14-year-old Elisabeth Paehtz and 15-year-old Irina Krush. The latter was also present at the launch on 21 June 1999 with a promotional event at Bryant Park in New York and became a leader during the chess game.

The game has been widely published and discussed, and there are numerous analyses and recaps. It is perhaps the most analysed game in the world, with the World Team using chess computers to predict moves.

Unreachable

For a long time Kasparov and the World Team were evenly matched. The then World Chess Champion later said that he had never put so much effort into any other game. And in the end – unlike the episode and celebration at Bishopwood – Kasparov won after 62 moves.

“It is the greatest game in chess history. The sheer number of ideas, the complexity and the contribution it has made to chess make it the most important game ever played”.

The chess notation found on the Bishopwood murder victims is not the chess notation of Kasparov’s game Versus the World. But this notation begins with the very classic Sicilian Defence:

E4 c5

Nf3 d6

D4 cxd4

Nxd4 Nf6.

Two racing celebrities: Isobel Hewitt…

Midsomer County is also home to two racing celebrities from the 1950s, both of whom celebrated victories at Silverstone in that decade: Isobel Hewitt and Duncan Palmer.

Unfortunately, we do not know exactly when and in which race Isobel Hewitt was so successful. We and Cully Barnaby only learn in passing from Dixie Goff that Isobel Hewitt celebrated a triumph as a racing driver at Silverstone. The Malham Bridge resident brings some old photographs to Cully’s mobile library in a caravan.

We learn a little more about Duncan Palmer, who won a Formula One race at Silverstone in 1960 or a few years earlier – ahead of Stirling Moss, the famous British racer of the 1950s.

In her private life, she drives a red Jaguar XK 120 O2S, which was manufactured between 1948 and 1954. It was Jaguar’s first sports car since 1939. The XK120 was launched in open two-seater and caused a sensation, which persuaded Jaguar founder and Chairman to put it into production.

… and Duncan Palmer

This is the opening sequence of John Barnaby’s first full-length case. (The first, after all, was the Badger’s Drift vicar’s hanging from the bell rope, which caused Tom Barnaby’s birthday and farewell party to be abruptly abandoned by his nephew and former colleagues).

We see a car race on a television set, recorded many, many years ago. The quality of the image and the racing cars make it easy to recognise. It’s a summary of a Formula 1 race at Silverstone. The commentator mentions this and mentions four of the drivers by name. Firstly the famous English racing driver Stirling Moss, but also Peter Fossett, Jamie Brooks and Duncan Palmer. Duncan Palmer narrowly wins the race against Peter Fossett. They knew each other well as they were both from Midsomer.

As Duncan Palmer died in a barn in 1962 in a Lotus X4, the F1 race must have taken place before that. And as not all British Grand Prix were held at Silverstone, and Sir Stirling Crauford Moss was active from 1951 to 1961, and Tony Brooks (who was apparently called Jamie Brooks in Midsomer?) from 1956 to 1961, the plausible races are 1956, 1958 or 1960 – always in mid-July.

When did Duncan Palmer won the Silverstone Grand Prix?

These races were won by Argentinean Juan Manuel Fangio (1956, Mercedes), Australian Jack Brabham (1960, Cooper-Climax) and Brit Peter Collins (1958, Ferrari).

So there are two plausible options for Midsomer’s Duncan Palmer: either the footage is from the 1958 Grand Prix and it matches his nationality, or it is from the 1960 Grand Prix and it matches the make of the car. What he has in common with Jack Brabham is that he competes with Brooks and Moss, and what he has in common with Peter Collins is that he died shortly after his triumph (Collins, however, was killed in the German Grand Prix just two weeks after his Silverstone triumph). In 1962 he was murdered in a barn near Midsomer-in-the-Marsh.

There is also a slight anachronism in the race commentary: Luffield Corner did not exist in the 1950s.

More Midsomer women in sport

Midsomer Wellow’s Frances Le Bon won the Inter County Championship as a markswoman – unfortunately no year is given.

So did Germaine Troguhton from Lower Pampling, who played cricket. She was very talented and captained the England women’s cricket team. It was probably in the late 1960s or 1970s.

In the Rowing Line

As well as being a ladies’ man, Midsomer Regatta’s Henry Charlton is also an ambitious rower who is being groomed for the Olympics by his coach, Clare Bonavita. She’s furious that she’s not allowed to coach him as an Olympian, but… it wouldn’t have worked either way, as she has to spend Charlton’s Olympics behind barred windows…

Henry Charlton has been compared to Steven Redgrave, who was a very good rower in the 1980s and 1990s, winning numerous medals and honours. Not only did he become world champion nine times between 1986 and 1999, but he also took part in five Olympic Games between 1984 and 2000, winning a gold medal each time:

- 1984 in Los Angeles: gold in men‘s four

- 1988 in Seoul: gold in men‘s coxless pair and bronze in men’s coxed pair

- 1992 in Barcelona: Gold in men’s coxless pair

- 1996 in Atlanta: Gold in men’s coxless pair

- 2000 in Sydney: Gold in men‘s coxless four

This last Olympic gold also earned him the title of Sportsman of the Year and a Knighthood the following year. (He had previously received an MBE in 1987 and a CBE in 1997).

In 2002, at the end of his career, he was awarded rowing’s highest honour, the Thomas Keller Medal.

I would be interested to know how Henry Charlton has fared in the meantime…

Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature

- Meredith, Anthony/Blackwell, Gordon: Silverstone and Formula 1. Stroud 2022.

- Meredith, Anthony/Blackwell, Gordon: Silverstone Circuit through time. Stroud 2013.

- Hackwood, Frederick W.: Old English Sports. London 1907.

- Manson, Iain: The Lion and the Eagle. Cheltenham 2008.

- NN: Warborough. In: Simon Townley (ed.): a History of the county of Oxford. Volume 18. Woodbridge, Suffolk 2016. P. 393-421.

- NN: Ready for a big chess match. In: New York Times (11/03/1894).

Further information

The full documentation of Kasparov’s game versus the world: Here you will find not only the recommendations of the four young chess geniuses, but also the moves that were on the ballot and their results. And that for all moves.

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 8 February 2024.

Updated on 16 February 2026.

6 thoughts on “Sports History in Midsomer, pt. 2: Other Sports”