•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episodes: S14E06: The Night of the Stag)

Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutsch.

•

On a colourfully decorated village square, a very well-attended, joyous fete takes place. There are stalls and plenty of alcohol to drink. We are at the Midsomer Abbas May Fayre, which is celebrated jointly by residents from Midsomer Abbas and Midsomer Herne – always on the first of May. Malmsey wine is served in a sweet version (= the well-known sweet Madeira wine) and in a tart version. Now, a man, Reverend Conrad Walker, enters the wooden platform and speaks into a microphone and welcomes the crowd.

There is vigorous applause as the two aldermen, Samuel Quested from Midsomer Abbas and Will Green from Midsomer Herne, come on stage. The Reverend meanwhile leaves the podium. Samuel Quested takes the floor and reminds the crowd of the spring of 1370, when there was a disastrous frost that froze all the apple blossoms and the inhabitants of Midsomer Abbas faced famine. The apple harvest was the main source of income for most of the inhabitants. But help came from neighbouring Midsomer Herne, who oddly seemed not to have had problems with frost, even though they live in the neighbouring valley.

They gave away their apples and established a friendship between the two villages.

The audience is cheering as Samuel Quested symbolically hands Will Green a basket of apples and the Reverend re-enters the stage and takes the microphone.

The Micro Famine?

In 1370 there were indeed crop failures in England, coupled with a new outbreak of the bubonic plague epidemic in 1369 – for the second time in England in the 1360s – and this during the Hundred Years’ War between England and France.

Well, apparently 1370 was not only a year in the middle of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France (1337-1453), but also a year with an even more amazing microclimate because the frost apparently stopped at the valley. (Both villages were apparently spared from the bubonic plague epidemic of that year. At least it is not mentioned).

However, the crop failure of 1370 is hardly mentioned in literature or even in contemporary sources. This is not so surprising because the plague of bubonic plague was probably many times worse. It was also apparently not as devastating as the Great Famine period of the 1310s, as the Dantean Anomaly is also called.

Dante Alighieri’s “Inferno” – a field report?

Dantean Anomaly – this term was coined by Oxford geophysicist Neville Brown in his 2001 book History and Climate Change.

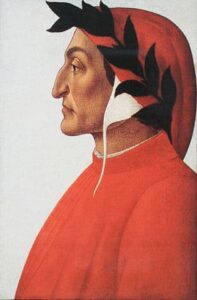

“Dantean” refers to the Italian author Dante Alighieri and his work “Inferno”, which has at least become world-famous since Dan Brown’s book of the same name.

In the last years of his life, Dante Alighieri experienced the Great Famine in Italy, which peaked there in 1310-1312. At the same time, he wrote his work for which he is still famous today: La Divina Commedia, the Divine Comedy. Researchers disagree on exactly when he began the work, but it was probably in the 1300s.

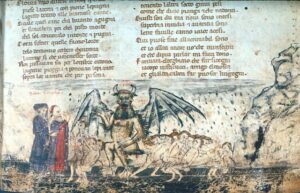

The first part of the Divine Comedy, the aforementioned “Inferno”, contains passages that seem like a result of his exuberant fantasy and fatalism, but were probably nothing more than his way of handling his real experiences:

“I am in the third circle, filled with cold, unending, heavy, and accursed rain; its measure and its kind are never changed. Gross hailstones, water gray with filth, and snow come streaking down across the shadowed air; the earth, as it receives that shower, stinks.“ (Inferno: Canto VI)

Crash weather events due to climate change

These extreme weather conditions occurred roughly from 1300 to 1325 and were by no means limited to England, the British Isles, or Italy. Rather, a total of 30 million people were affected throughout northern, central and, in some cases, southern Europe.

The 1310s in particular were a drastic climatic anomaly.

In the century before, an increase in solar radion and decrease in volcanic activity led to a warming and prosperous society throughout Europe with strong population growth, many new settlements and technical improvements in agriculture that made it possible to feed the population. This century of progress was then followed by periods of partly too much rain and partly too little rain from 1300 to 1325, leading into the Little Ice Age. The Dantean Anomaly was therefore nothing other than a sign of the blatant climate upheaval – which at that time led to an Ice Age.

Today we can only dream of that, although the weather events do not differ. Only we cannot expect the escapades of the climate to calm down again. The “Dantean Anomaly Junior Research Group“, a Europe-wide research project, is investigating the prehistory, development and effects 700 years ago and can already say: the weather events of the 1290s and around 2020 are damn similar. Then, as now, they were locally occurring weather events that could also differ greatly. For example, a Dominican monk from Colmar, Alsace, noted that the winter of 1303/04 was exceptionally cold in Rome, but much warmer than usual in Alsace. On the other hand, a year earlier the winter in Alsace was too cold and in Rome too warm.

The Dantean Anomaly in England

So what was the weather like during this climatic transition period in England? And can any references be made to the local weather of the filming location?

Filming took place in Oxfordshire, namely in Stanton St. John (Midsomer Herne) and Sydenham (Midsomer Abbas). Unfortunately, in the few weather records that have survived to the present day, location information is very rare. Therefore, I cannot say whether Sydenham or Oxfordshire in general was affected by a bad harvest in 1370, nor how the village or county fared during the Dantean Anomaly.

But let’s look at the weather of the years in England. I am mainly using a compilation of sources on the weather in England compiled by historian Katheryn Warner.

The consequence: The Great Famine

This frequent alternation of too hot and too dry, too wet and too cold weather led to massive crop failure, especially in 1314 and 1315. In 1315, floods destroyed one-third or one-half of the harvest. Famine was inevitable. Even King Edward had to go without food when he travelled to St Albans, as he had done so often before: There was simply no bread. It was not until 1317 that the harvest in England returned to normal, but food stocks were not fully replenished until 1322.

Across Europe, about 5-12% died in the two or three decades. Many animals also died of a highly virulent disease called murrains, which weakened the animals inexorably to the point of death – probably a kind of food-and-mouth. But people couldn’t even preserve the dead animals for their food, because salt was damp from the rainy season and also very expensive.

Parents gave their children away – not because they had a better chance of survival elsewhere, but parents only had a chance of survival if they didn’t still have children to feed. They needed the little food themselves in order not to starve. The world-famous fairy tale of Hansel and Gretel very likely originated during the Great Famine: the parents send the children off into the world, hoping they will never come back. Eventually they go to the house of a woman who is apparently so starved that she has become a cannibal.

Inflation and disease

However, it was not only the famine that caused concern, but also the political and social destabilisation of society and an inflation. The aristocracy had to watch the value of its domains collapse.

Land had to be sold, often at severely reduced prices, while many more would need to borrow to survive. Some small monasteries had to close, others sold relics to pilgrims.

The government thought it would be a good solution to install price controls and to import food from Southern Europe. Well, the rationing and regulation of food prices was a slight improvement for the consumers, but for the farmers it meant ruin because their businesses were no longer viable – and they could no longer support themselves. Therefore, the government lifted the price controls a few months later. This led to inflation and an eightfold increase in prices.

If it was “only” an outbreak of small-pox in England in 1305, the immunocompromised population throughout Europe was followed by the great plague epidemic, which occurred again and again locally until the 18th century. As elsewhere, it cost many lives immediately after the Great Famine because their immune systems had become weak from hunger. In England, the plague epidemic of 1349 alone cost 30% of human lives and was followed by others – five in the 14th century alone (1360, 1361, 1369, 1375, 1390).

The Papal Edict that Never Existed

Remember the Reverend Norman Grigor and his family’s appearance at the Midsomer Abbas May Fayre at the Domesday-like admonishing words he speaks?

He refers to the horn dance, a Beltane cult in which competing men with deer antlers go at each other to determine the strongest, most willing mate among themselves. Reverend Walker reassures us, however: this dance was toned down in the 1880s and is no more than a folk dance. We also see this in the episode.

John Barnaby later approaches Reverend Conrad Walker about these lines and Walker says they are part of a papal edict of 669 with which the Pope tried to put a stop to the pagan Beltane cult.

It should have been by Pope Vitalian at that time, but this edict does not exist. There was no edict in 669, nor was there ever an edict with this content. So it was only invented for dramaturgical reasons for the episode. But let’s be similar: it could very well have existed because there were numerous attempts at that time, as well as a thousand years later, to make the pagan cults absolete.

Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature

- Bauch, Martin: The “Dantean Anomaly” Project. Tracking Rapid Climate Change in Late Medieval Europe” (27/08/2016). In: Historical Climatology.

- Bauch, Martin/Labbé, Thomas/Engel, Annabell/Seifert/Patric: A prequel to the Dantean Anomaly. The precipitation seesaw and droughts of 1302 to 1307 in Europe. In: Climate of the Past 16 (2020).

- Brown, Neville: History and Climate Change. A Eurocentric Perspective. London/New York 2001.

- Buttery, Neil: The Great Famine (1315-1317). In: Climate in Arts & History.

- Frank, Robert Worth: Agriculture in the Middle Ages. Philadelphia 1995.

- NN: 10 Things to Know About the Great Famine. In: Medievalists.net.

- NN: The Great Famine 1315-1317. In: British Food. A History (09/09/2020).

- Pribyl, Kathleen: The Climate of Late Medieval England. Reconstruction and Impacts. Lecture at the Town Close Auditorium, Norwich Castle Museum, 2 November 2013. Based on: Kathleen Pritbyl, Rihard C. Cordes, Christian Pfister: Reconstructing medieval April-July mean temperatures in East Anglia, 1256-1431. In: Climatic Change 113 (2012). P. 393-412.

- Sharp, Buchanan: Royal paternalism and the moral economy in the reign of Edward III. The response to the Great Famine. In: Economic History Review 66 (2013), P. 628-647.

- Storey, R. L.: England. Allgemeine und politische Geschichte. Das Koenigtum im Konflikt mit Adelsgruppierungen. Der Hundertjaehrige Krieg. In: Lexikon des Mittelalters 3. Darmstadt 2009. Col. 1946-1958, here col. 1951.

- Warner, Katheryn: And Your Weather Forecast For The Early Fourteenth Century Is… In: Edward II (10/09/2009).

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 7 December 2023.

Updated on 20 January 2026.

6 thoughts on “The Night of the Stag”