•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episode: S07E02: Bad Tidings)

•

Sergeant Daniel Scott has just arrived at his new police station in Causton and is assigned to investigate a murder in Midsomer Mallow. Tom Barnaby and his new sergeant are walking across a meadow where a woman’s body has been found. Daniel Scott is struggling to walk on the uneven ground and in the tall grass. Meanwhile, Tom tells him that this place is called Chainey’s Field and has been common land for centuries – even in the Domesday Book.

In the background of the scene you can see a mansion, possibly the Spearmans’ house, which was filmed at Tyringham Hall in Cuddingham, Buckinghamshire. I’m not sure here, however, whether the large meadow referred to in the episode as Chainey’s Field is part of the Tyringham Hall estate. But a majority of the episode was filmed in various locations in Cuddingham and here, according to the Domesday Book, although there was no common field called Chainey’s field, the settlement of Cuddingham already existed. This included not one but two manors named after Tyringham: One was owned by Wiliam FitzAnsculf at the time of the records, the other belonged to the Bishop of Coutances. The present Tyringham Hall, built in 1792, has been on the National Heritage List since 30 August 1987.

England’s first land register

19 years after the Battle of Hastings, King William I ordered at Christmas 1085 – which was then the beginning of the year 1086 – in concern about a possible invasion from Denmark and Norway, to compile the own and annually taxable property of his subjects as well as accurate information about the military and other resources at his disposal.

This also included the annual value of every piece of landed property to its lord, and the resources in land, manpower, and livestock from which the value derived.

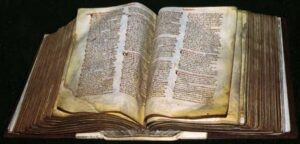

The Domesday Book is England’s first land register and consisted of money assessment lists. Indirectly, it was also the country’s first census. It is kept at The National Archives in Kew (London).

Completed in 1087

Collected were (1) lands, (2) their owners, and (3) the number of male inhabitants in most regions of England and parts of Wales. in order to fix in writing the taxes and dues. Further, the services due to the king, and the extent and value of the estates of the king’s direct liegemen.

The entries on the counties in the Domesday Book are mostly structured in the same way: A description of the royal boroughs and the royal sources of revenue at the time of the Battle of Hastings is followed by a list of the feudatories and a description of the demesne with its belongings. The terra regis, which was directly subject to the king, is described first, then the other fiefs in turn.

The result of the survey was that numerous sub-vassals held very large estates. William I demanded the oath of fealty from them, no matter whose liegeman they were.

The first survey was completed in 1087, but the book was not finished until after William I’s death in 1090. We now know that the survey was far less organised and systematically collected and compiled than previously thought. The methods used to collect the data have not been definitively clarified.

An big step for England

The compilation was an important step on the way to centralising power from local nobles to the royal court because before 1066 common law applied in Anglo-Saxon Britain: peasants and nobles owned land and rights that were not documented.

If Midsomer County existed, Chainey’s Field would already have been recorded as common land in this compilation. In reality, the Domesday Book recorded a total of 268,984 male heads of households in 13,418 places, from which the full population figure can be calculated: an estimated 1.2 and 1.6 million people lived in the area covered by the Norman Land Register. It can also be seen that land use was fairly evenly divided with a slight majority at 35% arable land.

Basically all land belonged to the king according to the fief pyramid, but only 17% was in direct access as 54% belonged to the eleven tenant-in-chiefs of William I, almost all of whom were blood relatives of him: Odo of Bayeux, Robert of Mortain, William FitzOsbern, Roger de Montgomerie, William de Warenne, Hugh d’Avranches, Count Erstach III of Boulogne, Alain the Red Earl of Richmond, Richard FitzGilbert, Geoffroy de Monbray, Geoffrey de Mandeville. We have already met the Richards and Williams in the chapter on the Battle of Hastings. These eleven men were subject to over 100 manors. The remaining 26% were owned by Norman bishops and abbots.

Eternal validity

The undertaking was contemporary without parallel. Originally, the compilation was called “Liber de Wintonia”, i.e. “Book of Winchester” The name Domesday Book only came into being a century after its completion, because the results of the nationwide investigation were to be valid until the end, i.e. until Judgement Day. The Old English term “doom” meant nothing other than law or judgement.

Nevertheless, it stands to reason that Richard FitzNeal had the end of the world in mind. Within the first thousand years after Christ’s birth, there had been repeated signs and calculations of the end of the world. And just in the year 1179, in which FitzNeal made the “Domesday Book” out of “Liber de Wintonia”, the astronomer John of Toledo predicted the end of the world for 1186: all planets would be in the constellation Libra from 23 September 1186 – that was a sure sign of the end of the world. What might make us smile today triggered a European mass panic at the time. The Byzantine emperor, for example, had all the windows of his palace bricked up.

Additional information

About the Domesday survey: In addition, the “little Domesday” Book was added for Norfolk, Suffolk, and Essex. Not included were the later Westmorland, Cumberland, Northumberland, and County Durham because they did not pay the national land tax called the geld. Extra space was left for London and Winchester, but not filled.

About the eternal validity: Richard FitzNeal in the Dialogus de Scaccario (1179): „unalterable“, „its sentence could not be quashed“, cf. Johnson, C. (Ed).: Dialogus de Scaccario, the Course of the Exchequer, and Constitutio Domus Regis (= The Establishment of the Royal Household, Oxford Medieval Tests). London 1950. P. 64. In fact, there were no further such surveys in England until 1873. Cf. Hoskins, W. G.: A New Survey of England: Devon. London 1954. p. 87. The “Return of Owners of Land” of 1873 was also called “Modern Domesday”.

Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature

- Darby, Henry Clifford: Domesday England. Cambridge 1986.

- Harvey, Sally: Domesday. Book of Judgement. Oxford 2014.

- Hoskins, W. G.: A New Survey of England: Devon. London 1954.

- Johnson, C. (Ed.).: Dialogus de Scaccario, the Course of the Exchequer, and Constitutio Domus Regis (= The Establishment of the Royal Household, Oxford Medieval Tests). London 1950.

- NN: Life in the 11th Century. In: The Domesday Book Online.

- Stenton, Frank Merry: Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford 1971.

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 22 December 2023.

Updated on 15 June 2025.

28 thoughts on “Domesday in Midsomer”