•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episode: S12E04: The Glitch)

Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutsch.

•

The Midsomer Cycling Club from Aspern Tallow – adults and young people – often go cycling, today along the old pilgrim route to an old church ruin. On the top of a hill they take a short rest. Down in the valley, the destination is already in sight: The Abbey of St Frideswide in the Valley of Midsomer Sanctae.

While some of the children continued to cycle at a fast pace, the adults stopped to chat. George Jeffers interrupts their conversation to look down at the ruins of the church.

Arriving down at the ruins, the young people and we learn a little more about the former church, thanks to George Jeffers: Pilgrimages from Causton to this abbey to pray to St Frideswide began over 700 years ago. Before that there was a Roman shrine on the site, and before that a Celtic shrine.

St Frideswide, patron saint of Oxford

It is recorded that Frideswide was the daughter of an Anglo-Saxon king. However, as is often the case, not much more is known about the saint.

The story goes that Frideswide was educated by a very Christian governess. Here she learned to love and live the Christian faith and decided to lead a spiritual life in the future. She did not become a nun, but simply lived a self-chosen life of seclusion and chastity in a religious retreat with twelve other women.

Meanwhile, the royal Mercian prince Aelfgar was courting Frideswide. To summarise the story (based on Berkshire History): Frideswide refused repeated messages of love and gifts of love, enraging Prince Aelfgar, whose honour was offended. The second time Aelfgar rode to Frideswide in anger, she had already fled Oxford with two other women to what is now Berkshire. Here they hid in the deep oak forest and built a small oratory.

But the people of Oxford betrayed their hiding place when Aelfgar threatened to reduce the city to rubble. Frideswide prayed to St Catherine and St Cecilia for her life and a miracle happened: when she was within reach of the Mercian prince, he suddenly went blind and fell off his horse into the mud. He begged for forgiveness and swore to do penance. She took pity on him, bathed his eyes and prayed for his sight – and it returned. She lived in Oxford for many years.

Contemporary with Frideswide’s life: The Christianisation of the Anglo-Saxons

By the 5th century, the Roman Empire could no longer be maintained in Britain. Power increasingly passed to Romanised princes (‘reges’) and native aristocrats. At the same time, people arrived from Jutland and the Angles, as well as immigrants from the Frisian area – the Saxons. Unlike the Romanised English, they were not Catholics but pagans. These pagan beliefs were adopted more and more in the following decades, but finally the Christianisation of the Saxons (today: Anglo-Saxons) took place in the 7th century.

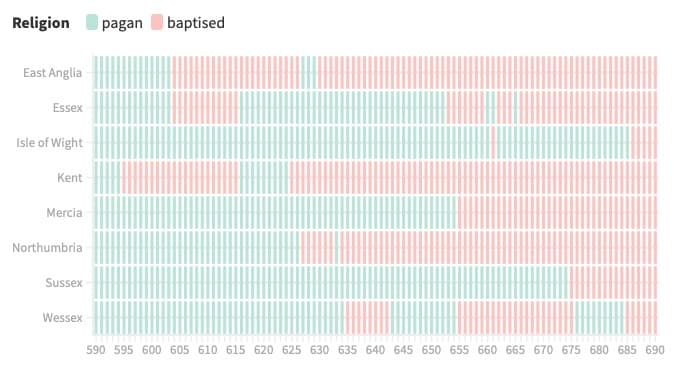

This Christianisation was neither uniform nor unique. Depending on the ruler of the region, the faith changed from pagan to baptised several times during the 7th century. Sometimes even within a single regency.

This chart shows the back and forth of the Anglo-Saxon faith. It also shows that by the time Frideswide was born, sometime between 650 and 700, the Christian faith was already more and more widespread.

By 660 there were Christian communities in every English kingdom, but the English Church was divided and not well organised. It was in danger of collapsing. There was also an outbreak of plague in 664 which killed many Christian clergy, including Bishop Deusdedit of Canterbury.

Pope Vitalian sent two bishops from Italy to southern England to fill Deusdedit’s vacancy and provide general stability. Theodore became the new Bishop of Canterbury in 668, and Hadrian accompanied him on his journey. A journey that lasted a whole year. Then Theodore and Hadrian went on a tour of England to assess the state of the English Church, and it was not a pleasant one. So Theodore appointed himself archbishop and filled many vacant sees with new bishops. He also took the first steps towards taking over the Roman Catholic Church in England.

This also affected the way people were buried.

Missionary work in the 6th century

A hundred years earlier, a major missionary campaign against the pagan Britons had failed. It was a missionary campaign by Pope Gregory that provided the impetus for the gradual Christianisation of southern England. His efforts were prompted by the marriage between the pagan Æthelbert of Kent and the Christian Merovingian Bertha sometime before 597. Æthelbert tolerated Bertha’s religion and converted some years after the marriage.

We can only speculate about the reasons for Gregory’s mission and Æthelbert’s conversion. Were they religious or political? What part did the Merovingians play, or Bertha of Kent?

Pope Gregory’s choice of Augustine for missionary work in the south of England was, of course, no accident. Augustine had previously been prior of Pope Gregory’s own monastery in Rome.

Gregory gave Augustine the power of a metropolitan archbishop of the southern part of the British Isles, with the help of the Merovingians. But by this time the long-established Celtic bishops, in a series of meetings, refused to recognise his authority. After the Roman legions had left, the Christians remained in Britain and – because of their distance from Rome – developed their own distinctive practices! of Celtic Christianity. These included the different calculation of Easter, the emphasis on monasteries rather than bishops, and other things like clerical tonsure.

Worship of Frideswide

The monastery founded by Frideswide in Oxford is said to have been destroyed in 1002. An Augustinian canonry was built on its walls until 1122, when it was converted into a secular canonry. The patrocinium remained with St Frideswide and from 1180 her bones were moved as relics from her tomb to the collegiate church, which became a place of pilgrimage. She also became the patron saint of the city of Oxford and Oxford University.

In 1525 the monastery was dissolved by Cardinal Wolsey and transformed into Cardinal’s College with the Abbey Church as the college chapel. Funds from the dissolution of Wallingford Priory and other priories were used to dissolve Waverley Abbey.

Five years later, however, Cardinal Wolsey fell out of favour with King Henry VIII. In 1546, the King took over the nascent foundation and converted the collegiate church into an Anglican cathedral and the patron saint from a Catholic saint to Christ – it is now Christ Church Cathedral in Oxford.

Frideswide’s small oratory in the former oak forest of Berkshire is also a place of pilgrimage. There is a chapel at Frilsham, but it dates from Norman times. It may, however, stand on the ruins of an Anglo-Saxon oratory.

Waverley Abbey

Both churches, Christ Church Cathedral in Oxford and Frilsham, are further away from the filming location.

The ruins of Waverley Abbey, 32 miles (51 km) from Frilsham and 49 miles (79 km) from Christ Church Cathedral in Oxford, were used for this location.

Founded in 1128, it was the first Cistercian monastery in the British Isles. Its mother monastery was the monastery of L’Aumône in Normandy, dedicated to St Mary. “The Abbey of the Blessed Mary of Waverley was its full name.

But it lasted only 400 years and was largely demolished at the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536). The ruins were used as a quarry over the next few centuries, including for Loseley House.

Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature

- Blair, John: St Frideswide’s monastery- Problems and possibilities. In: Oxoniensia 53 (1988). P. 221-258.

- Higham, Nicholas J.: The Convert Kings. Power and Religious Affiliation in Early Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester 1997.

- Hindley, Geoffrey: A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons. London 2006.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry: The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. 3rd Edition. London 1991.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry: Functions of a twelfth-century shrine. The miracles of St Frideswide. In: Henry Mayr-Harting/R. I. Moore (Ed.): Studies in medieval history presented to R. H. C. Davis. London 1985. P. 193-206.

- Nash Ford, David: St. Frideswide – Folklore or Fact? In: Royal Berkshire History.

- Nash Ford, David: St. Frideswide. Patroness of Oxfordshire or Berkshire? In: Berkshire History.

- Reames, Sherry L.: The Legend of Friedeswide of Oxford. An Anglo-Saxon Royal Abess. Introduction. In: Sherry L. Reames (Ed.). Middle English Legends of Women Saints. Kalamazoo 2003.

- Willoughby, James: Thomas Wolsey and the books of Cardinal College, Oxford. In: Bodleian Library Record 28 (2015). P. 114-134.

Further recommended reading

Scholarly studies on early Christianisation around 600 and the back and forth afterwards

- Vosper, Emma: Migration and conversion. The Christianisation of Britain. In: Our Migrationstory (ohne Datum).

Comparison of the sources and manuscripts

- Reames, Sherry L.: The Legend of Frideswide of Oxford. An Anglo-Saxon Royal Abess. Introduction. In: Sherry L. Reames (Ed.). Middle English Legends of Women Saints. Kalamazoo 2003.

There are still desiderata for research on St Frideswide. John Blair addresses these in great detail and depth in two essays

- Blair, John: Saint Frideswide Reconsidered. In: Oxoniensia 52 (1987). P. 71-127.

- Blair, John: St. Frideswide’s Monastery Problems and Possibilities. In Oxoniensia 53 (1988). P. 221-258.

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 2 February 2024.

Updated on 20 January 2026.

21 thoughts on “Saint Frideswide”