by Petra Tabarelli

Also available for download as a PDF file here.

Estimated time to read: 30-35 minutes

This text is basically like an essay, but it doesn’t have to fit into any particular genre. Instead, it’s the thoughtful musings of a cultural historian who’s well-versed in England’s Romantic imagery of the rural idyll, and who’s also a fan of Midsomer Murders.

So, I’m basically going to take you on a journey through my thoughts, my reading notes and my observations.

Foreword: Englishness, a peculiar term

Englishness. In 2025, the term is prominent in public debate in the UK, but not in a positive sense. Although the concept is essentially neutral, it is currently being used by some conservative voices to paint a nostalgic fantasy of England. The catalyst was an article by former Home Secretary Suella Braverman in February 2025. Despite being born and raised in England, she wrote that she did not consider herself ‘English’, claiming that true Englishness must be rooted ‘in ancestry, heritage, and, yes, ethnicity’. Citizenship, residence, or language skills are not enough.

This view caused widespread controversy, with accusations that it reduced Englishness to ethnic and cultural purity, thereby excluding many people of migrant background. The discussion emerged at a politically charged moment, in a climate receptive to controversy on British identity.

By the end of 2025, there is still no clear consensus. A YouGov study on ‘Race, heritage and British/English identity’, published in November 2025, illustrates that many UK-born adults with a migrant or minority background see themselves as British rather than English’ The survey shows that many Britons understand ‘Englishness’ in cultural terms, but a significant proportion also share Braverman’s view.

Discussions about the concept of Englishness are certainly nothing new, nor are they happening for the first time in 2025. However, this makes it very difficult to use ‘Englishness’ in a neutral way. For that reason, I will use the term cultural memory of England. This term is not related to ethnicity or blood, but rather to atmosphere, emotion and the power of a shared imagined past.

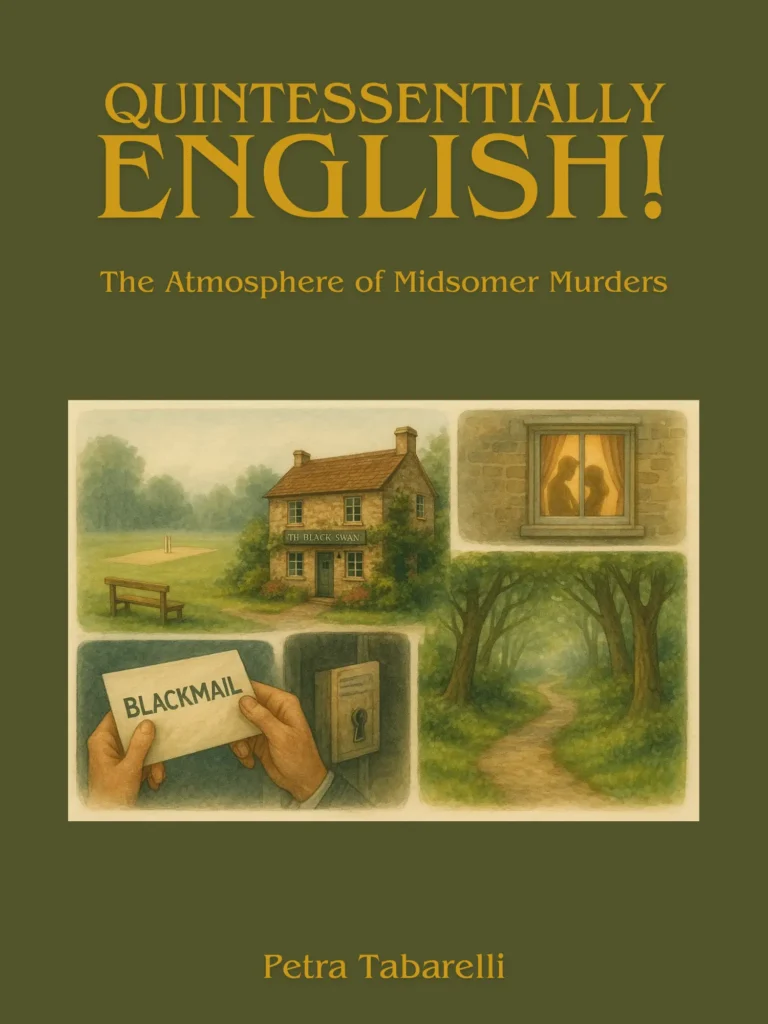

Quintessentially English: The Atmosphere of Midsomer Murders

Introduction: A Question in the Mist

But what exactly constitutes the cultural memory of England? What do we mean when we describe Midsomer Murders being quintessentially English?

It is hard to disagree with the idea of this series as quintessentially English. Without hesitation, most people would list various elements that prove this, such as thatched cottages and stately manors, village cricket on the village green, lanes with overhanging hedgerows, village churches with weathered doors and old gravestones, charity work, village competitions, fêtes and carnivals, Victoria sponge cake, shepherd’s pie, tea and biscuits, and artistically decorated sandwiches. The list would be very long indeed.

But what is the most quintessentially English thing? Perhaps it’s the moment the UK voted for the greatest TV show ever. It is not a historical moment, a landscape or a type of food. It’s a constructed, staged semi-reality that clearly touched the British public.

The 2012 Olympics. A car drives through the gates of Buckingham Palace. A group of schoolchildren are being given a tour when a man gets out of the car and their attention is diverted. Accompanied by two corgis, he walks briskly into the palace to her room.

She is writing a letter at a desk and does not notice him arrive. He has to clear his throat to get her attention – and the Queen turns to James Bond. In fact, it is Daniel Craig to whom Queen Elizabeth II turns, while the camera, lights and microphone are focused on her. Reality and staging merge. We see James Bond, not Daniel Craig. On the other hand, it is actually Queen Elizabeth II herself, rather than an actress who looks like her. This is precisely why the scene has such an intense effect: it is staged on the very edge of reality.

A similar thing happened a few years later at the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee, when she received a visit from the clumsy Paddington Bear.

One way of thinking about this cultural memory is as a form of ‘collective nostalgia’. It does not only affect one person but is the nostalgia of a group or a culture. It shapes identity, i.e. it provides a certain framework for a group.1

But what is nostalgia anyway? It is an emotion, a memory; a longing for a feeling, and it consists of stories about our past. It is the remembrance of the past from the present perspective, and memories often fade. Only the good ones remain, evoking the ‘good old days’, which, not without reason, are usually the days of our youth. Back then, life was more carefree.

Though the ‘good old days’ are a construct, and nostalgic feelings can vary based on gender and age. The world was neither better nor worse than it is today.

In her book The Future of Nostalgia, cultural theorist Svetlana Boym wrote: ‘Nostalgia arises from the fusion of actual and mental landscapes.’ This is somewhat abstract, but it essentially describes what augmented reality offers: for example, the Pokémon Go app allows to see the real environment (‘actual landscapes’) as well as a Pokémon that is not actually there (‘mental landscapes’). It is like visiting a castle and imagining what it might have looked like in the Middle Ages. Or when James Bond accompanies the real Queen at the Olympic opening ceremony.

It is like an extra layer added to the past or to reality.

As nostalgia is primarily associated with memories and feelings rather than historical facts, it often arises from sensory experiences, such as seeing a photo of someone we like very much. A video in which we hear the voice of a beloved deceased person and see their movements. Or a meal that we haven’t eaten in a long time because an ingredient was unavailable or the recipe was lost.

However, this is personal nostalgia, fed primarily by memories from one’s own childhood and youth, rather than collective or cultural memory.

An example: in the first volume of his multi-volume autobiographical novel In Search of Lost Time (original title: À la recherche du temps perdu), Marcel Proust recounts something he experienced in 1909. I quote this passage at length because Proust captures this nostalgic experience so precisely:

[My mother] sent out for one of those short, plump little cakes called ‘petites madeleines’, which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted scallop of a pilgrim’s shell. And soon, mechanically, weary after the dull day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate than a shudder ran through my whole body, and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary changes that were taking place. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. It had immediately made me indifferent to the vicissitudes of life, its disasters harmless, its brevity illusory, in the same way that love operates, filling me with a precious essence: or rather, this essence was not in me, it was me. I had ceased to feel mediocre, contingent, mortal. Where could this powerful joy have come from? I felt that it was linked to the taste of tea and cake, but that it went far beyond that, that it could not be of the same nature. Where did it come from? What did it mean? Where could I grasp it?2

That is the epitome of personal nostalgia. In this case, nostalgia can provide psychological support because, even though the memory is bittersweet. It is uplifting and gives confidence, forming a basis for the future. It’s as if the past exists in the present, ready to be passed on to the future. Like a family heirloom.3 Svetlana Boym refers to this in her work as ‘reflective nostalgia’: a nostalgia that acknowledges the irretrievable nature of the past.

In contrast, what Boym calls ‘restorative nostalgia’ is the desire to restore a memory. This reflects a culture that has detached itself from its past and wants to recreate an idealised version of it. Restorative nostalgia believes in returning to old values or creating an ideal world. However, the problem is that it seeks to recreate memories and feelings to revive a past that never existed. This approach only leads to anachronism.4

A classic case of restorative nostalgia: clinging to a romanticised memory that one tries to keep alive, or even reactivate, despite it never having existed in that way. It is a misremembrance; a search for a fictitious past rather than an accurate memory.

There are various examples of this in the series, three of which are mentioned here as examples: Honoria Lyddiard is very obviously stuck in restorative nostalgia with Ralph and denies his sexual identity (Written in Blood, S01E01). Or Sylvia Lennard, who is determined to restore Little Auburn as a living museum, just as it was in 1942 (The Village That Rose from the Dead, S19E01). Or two episodes later in ‘Last Man Out’ (S19E03), when Ben Jones returns to Midsomer undercover shortly after: Germaine Troughton wants to preserve the classic game of cricket at all costs, which she occasionally captains as captain of the English women’s national team. Only at the very end does she painfully realise that the future cannot be stopped and that she has made some mistakes in recent years.

But since when has there been a cultural memory of England? What defines it?

Chapter 1: The Green and Pleasant Land

This question is not only difficult to answer; it resists any precise answer. One possibility is the fifth century, when the Anglo-Saxons first settled in Britain. Or perhaps the 12th century, the time of Richard the Lionheart? Or the 16th century, with the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Shakespeare, and Henry VIII? Or even later?

All of these events make sense. The Dissolution of the Monasteries is mentioned several times in Midsomer Murders for good reason. And there is Cully, who mainly performs Shakespeare’s plays.

However, I would like to mention two historians from Midsomer County here, a married couple in the episode ‘The Silent Land’ (S13E04). The historians in question are Faith and Ian Kent. Their historical focus is, at its core, entirely English, yet as different as it could possibly be. While Faith is interested in the local history of March Magna and of St Fidelis Hospital in particular, her husband merely wrinkles his nose in distaste and remarks that he despises everything Victorian – the attitudes, the kitsch, the cloying sentimentality. His areas of expertise are the Tudor constitution and Renaissance English literature. Faith’s interest in the events of the Romantic period and the Victorian era in relation to local history contrasts with the focus on national history.

On the one hand, there is legal tradition, parliamentarianism and literary English high culture. On the other hand is a focus on Romanticism and the Victorian era. While Faith is portrayed as a rather likeable character, Ian is not. I dare say this is no coincidence, as the period in which Faith is interested is crucial to the atmosphere of Midsomer Murders.

This is yet another reason why I am reluctant to define the cultural memory on which it is based in terms of Henry VIII and Shakespeare.

It is not only the episode in which Joyce Barnaby is convinced she has hit someone with her car, but also the one centring Caroline Maria Roberts, a tuberculosis patient who attempted suicide at Saint Fidelis Hospital for Diseases of the Chest in March Magna in 1875. At that time, England was experiencing significant upheaval. Urbanisation, impoverishment, and the exodus of people from the countryside to the emerging cities had been ongoing for a century or so, but by the Victorian era, these trends had reached their peak. During the previous century, the British Romantic period, artists in particular created the idealised image of the English landscape: tranquillity, green hills and small, idyllic villages where traditional England resides. Painters such as John Constable and William Turner – and in Midsomer County, Henry Hogson (The Black Book, S12E02) – as well as poets such as William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Blake, shaped the Romantic gaze.

In ‘Blood Will Out’ (S02E04) Tom Barnaby warns the travelling community that he will not tolerate theft, fighting or the dumping of rubbish ‘on England’s green and pleasant land’. This is a quotation from William Blake’s satirical poem And did those feet in ancient time, which was set to music by Sir Hubert Parry in the hymn Jerusalem in 1916 and became a patriotic anthem.5

England – this is equivalent to the rural idyll, the countryside. Romantic landscape ideals take old and new motifs, such as classical landscape painting and pastoral poetry, and transform them. Examples include the terms ‘the sublime’ and ‘the beautiful’ (Edmund Burke, 1757) and ‘the picturesque’ (William Gilpin, 1782), which were used to describe and classify landscapes during the Romantic period in Great Britain and abroad.

Romantic greats such as William Turner do not appear in Midsomer Murders, but a Midsomer celebrity was invented for ‘The Black Book’ (S12E02): Henry Hogson (1742–1810), a renowned 18th-century landscape painter who lived and worked in Midsomer County.

The villagers held Hogson in high esteem because, although he was an early Romantic, he was also a social realist with subtle social criticism in his work. For example, in The Parson Preaching, he depicts the eloquent retired clergyman Parson James, who has been swindled out of a fortune by his congregation. The painting is beautiful and idyllic. However, Parson James’s gaze is fixed on an old woman’s purse.

Although Hogon is a fictional character, could a real painter from that period have served as a model for him? Perhaps Turner? Or what about Constable, who is briefly mentioned in the episode ‘Painted in Blood’ (S06E03) in Sergeant Troy’s pun? I would rather place him somewhere between the watercolour landscape painter David Cox (1783–1859) and the socially critical rural life painter George Morland (1763–1804). Hogson and Morland’s gloomy premonitions worsened in the second half of the 19th century. the industrial revolution and the rapid advances in technology, the Victorian era also witnessed a significant shift in rural society: urbanisation. Impoverished people fled the countryside for the emerging industrial centres. This occurred not only in Great Britain, but also on the European continent, albeit not to the same extent. The exodus from the countryside was so significant in Great Britain that cities, especially London, grew rapidly. In 1750, around 80 per cent of the population of England still lived in rural areas. By 1900, the proportion had almost reversed, with about 80 per cent living in towns and cities. This gradual shift became a mass exodus – a demographic revolution in just two generations.

Alongside this wave of migration, a new social structure emerged in many cities: the growing industrial proletariat often lived in overcrowded dwellings and the inadequate infrastructure led to misery, health problems and poverty.

Then came the First World War, which acted as a catalyst. Not only did it bring the issues of death, dying and physical injury directly to people’s attention, it also brought about an agricultural depression. This mainly affected families who had invested all their money in land.

The situation intensified in the 1930s, when former tenants who had bought their land found themselves in debt, while agricultural lease prices remained low, pushing many farms to the brink of collapse.

In summary: England’s rapid urbanisation took its toll on rural communities, prompting the use of the term ‘depopulation’. It was a time of radical change and disillusionment. This provided the ideal conditions for the idealisation of rural England, which became the moral, aesthetic and spiritual basis of England’s cultural memory. This emerged in the 20th century and continues to influence the present day and beyond. This rural idyll was not perfect, but it was natural and unspoilt.

This brings us straight to the atmosphere of Midsomer Murders.

Chapter 2: Memories of an England that Never Existed

The 1950s are usually seen as the reference point for Midsomer, yet I would shift the emphasis slightly. Let me briefly explain why: The ‘Englishness’ of the 1950s was virtually a carbon copy of the constructed ‘Englishness’ of the interwar period because, at that time, people longed for the ‘good old days’ before the Second World War.

Remember: nostalgia often arises from farewells, particularly after major upheaval. When an entire society is shaken – as in a war – and not just individual lives, the instinct is to look back on the time before things changed.

After the Second World War, this took a very specific form. In the 1950s, England looked back to the interwar period not to recreate it, but to draw strength from the atmosphere of that time. This was largely reflective nostalgia, a way of stabilising and facing the future without being overwhelmed by what had just happened.

But it was not only the 1950s that began in shock; the interwar period itself did too. The trauma of 1914–18 was added to decades of social and technological upheaval since the mid-19th century, including urbanisation and the accelerating pace of industry. This created a sense that life was spinning out of control. In this context, nostalgia reached even further back – not to the early 20th century, but to the Romantic period before 1850. Unlike the 1950s, this was not a gentle reflection; but restorative nostalgia. Interwar period saw the construction of an anachronistic rural dream: a serene, unspoilt countryside where English identity, the land, peace, and stability were one and the same.

In 1924, Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin summed up this sentiment in a single line: ‘England is the countryside, and the countryside is England.’ The countryside became a place of healing and pilgrimage, particularly for city dwellers worn down by noise, work, and the fast pace of life. Early motoring culture capitalised on this idea: advertisements encouraged people to drive out of the city for a short weekend break, to experience an idyllic, ‘timeless’ England, and to return on Monday feeling restored.

In effect, it was a secular pilgrimage. In this supposedly unspoilt landscape, people felt close to their origins as Arthur Gardner wrote in Britain’s Mountain Heritage in 1942:

When we think of England, we do not picture crowded factories or rows of suburban villas, but our thoughts turn to rolling hills, green fields and stately trees, to cottage homes, picturesquely grouped round the village green beside the church and manor house.6

The promise is that of peace, idyllic surroundings and unspoilt nature. As this cultural memory is based more on emotion than facts, it represents nostalgia more than the post. This gives it this typical timeless quality that enables it to endure over time.

Bekonscot, located in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, is the world’s first model village. It was created by Roland Callingham and opened in 1929. It perfectly captures the essence of the idealised English nostalgia of the interwar period. It is no wonder that it was also used as a film location for an episode of Midsomer Murders: ‘Small Mercies’ (S12E05) starring Olivia Colman.

Like Bekonscot, the landscape of Midsomer in the TV series not only acts as a character in its own right and as an allegory for the idealised image of the English village: churches surrounded by cemeteries, miles of wheat and barley fields, a few rapeseed fields, village greens where people play cricket, and thatched cottages.

At the heart of this community lies the village green, where fêtes and other festivities take place. The village shop and post office act as social hubs, bringing people and information together and spreading them throughout the village. Similarly, every family is a small community within the wider village community, with the village, with the hearth at its centre, as the Fluxes explain in ‘The House in the Woods’ (S09E01).

It is a system, in which humans and nature live in harmony, naturally shapes the way people live together in a village. In the early series in particular, the theme of the villagers’ community life is explored.

Several scenes depict the villagers helping each other and forming a community. Especially in the first series, the coexistence of the people in the village as a community becomes a theme, particularly in DCI Tom Barnaby’s interviews to ensure that there is nothing unusual in this village and that everyone gets along very well with everyone else. By this I mean phrases such as ‘Well, we have to help each other, don’t we? That’s what living in a village is all about.’ (S02E01: Death’s Shadows) or ‘Midsomer Mallow isn’t just a village, it’s a community.’ (S03E03: Judgement Day).

Midsomer is not set in a particular place, nor does it take place at a specific time. Because it is timeless, Midsomer can inhabit the 1920s, 1950s, 1980s and present day simultaneously. It is a kind of pastiche, a memorial to an atmosphere created through selected houses, streets and landscapes on screen, and through persistent evocations of the 1920s and 1930s in the novels.7

Let us look at ‘The Killings at Badger’s Drift’ as an example: Although Caroline Graham’s characters do not all inhabit the same nostalgic time zone, each one cherishes their own ‘memories of youth’ and ‘good old days’ which together form one part of the atmosphere of Midsomer Murders:

Lucy Bellringer, one of the village’s oldest residents, fondly reminisces about 1920s England: chintz fabrics, lace blouses and her somewhat old-fashioned accent. Last but not least is the yellowed photo of her with Emily Simpson in the summer of 1924, which points to a bygone interwar era. This private archive of memories is evident even in her description of Emily Simpson’s house, which DCI Tom Barnaby, who knows the interwar period only through stories, sees as the perfect backdrop to a bygone era.

Tom Barnaby himself has his own nostalgic reference points to the 1950s. He reminisces about simple things, like as finding salted beans in the pantry and being reminded of his mother or chewing on hawthorn and calling it by its folk name, ‘bread-and-cheese’ – and the sobering realisation that it no longer tastes the way he remembers. Joyce Barnaby, Henry Trace and other characters share this post-war nostalgia, which is evident in their clothing, furnishings and everyday rituals.

Sergeant Gavin Troy, on the other hand, was born in the 1950s and represents the next generation. His perspective is yet another. To him, Lucy’s chintz and her jet-adorned mourning hat are as foreign as Barnaby’s childhood memories.

This overlapping of personal nostalgia creates not a boundless dreamtime, but rather a dense palimpsest: interwar and post-war nostalgia; objects of memory, such as Emily Simpson’s Bakelite telephone or Lucy Bellringer’s obligatory ‘shooting stick’; and projections all intertwine.

After this wander through memories, let us return to the idyllic atmosphere of Midsomer Murders. Although it seems idyllic at first glance, we know that the harmony is only skin deep. Beneath the surface, dangerous tensions are simmering.

Chapter 3: Caroline Graham’s Masterpiece

At the end of the episode ‘The House in the Woods’ (S09E01), Tom Barnaby quotes from Philip Larkin’s poem Going, Going (1972):

And that will be England gone.

The shadows, the meadows, the lanes,

the guild halls, the carved choirs.

For readers who are not from England: the term Tudor constitution refers to the structure and practice of governance, law, and administration during the Tudor period (1485–1603). It is often used as an origin story for the later self-image of the English state as a monarchy, parliament, and law.

Renaissance English literature encompasses the works of Shakespeare and the Jacobean tragedies. This period is widely regarded as the golden age of English poetry, with Shakespeare at its heart.

Larkin was a well-known post-war English poet who greatly admired Thomas Hardy, helping to bring him back into the public eye. Hardy’s poems are interwoven with melancholy because he observes life with an awareness of its transience. Every moment of joy carries within it the shadow of its end. This becomes clear when we look at his poem Weathers (1922), which DCI Tom Barnaby quotes in ‘The Glitch’ (S12E04):

This is the weather the cuckoo likes

And they sit outside at the Traveller's Rest

And maids come forth in sprig-muslin drest

And citizens dream of the south and west

And so do I

The subtext is: when the women go out in their sprig-muslin dresses, everyone knows the rain will soon return. How beautiful – and how fleeting. This kind of melancholy is nostalgia in advance; a sense that joy will soon disappear. This is typical of Hardy. His poems breathe the atmosphere of rural England after urbanisation and the First World War. This melancholy and sense of impending loss in Hardy’s work can also be seen in the lines quoted of Larkin’s poem. Going, Going is not romanticised nostalgia for the countryside. Rather, it is a swan song that reveals Larkin to be one of those Englishmen who mistrusted the future, was attached to the past, and felt a sense of loss of tradition in the face of seemingly endless change and urban sprawl. In short, he could not easily bear the demands of the present. This is the perfect breeding ground for restorative nostalgia: a fixation on a romanticised past that has long gone, which people have tried (and still try) to reactivate at all costs. Although time has long since moved on. Restorative nostalgia is a key feature of the conservative-to-right political spectrum, promoting the idea of a stable past and creating a stable political identity in the present.

Philip Larkin’s rancour expressed a profound cultural shift in mood and foreshadowed Margaret Thatcher’s ideology: In 1979, she became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and her eleven-year premiership defined what became known as Thatcherism. Like all words ending in ‘-ism’, Thatcherism was one thing: too much. There was too much privatisation, too much neoliberal harshness, too much radicalism in the market economy, too many double standards and too much class division. And Thatcher’s concept of heritage was, above all, about the cultural memory of 1950s England. This is hardly random; it was the time of her youth and her first decade in politics. She brought about a renewed reconstruction of ‘Englishness’, reaching back to the interwar ideal – a constructed vision of a countryside where identity, virtue, calm and even God were believed to dwell. However, Thatcher distorted this image by associating it with what she termed ‘Victorian values’, i.e. pre-capitalist values such as traditional family structures, self-reliance, hard work and harsher punishment. Crime was pathologised and considered as a hereditary disease and neighbourhood watches became a form of privatised social control.8

So let us compare these two types of England’s cultural memory – the interwar period and the 1980s. Although both draw on similar images, such as villages, country houses, tradition and the empire, they have very different purposes, ideals and inner rhythms.

Rurality

1920s: a place of inner peace rather than political power

1980s: the ideological domain of the ‘true English’

Tradition

1920s: meaningful, not stabilising rule

1980s: a politically charged identity, ‘back to basics’

Morality

1920s: rather implicit, as a habit and attitude rather than a set of rules

1980s: codified as achievement, property and personal responsibility

Cultural attitude

1920s: melancholic and conservative, but without harshness

1980s: restorative, proud and exclusive, often xenophobic or anti-modernist

What is the purpose of Englishness?

1920s: an inner retreat following the loss of the First World War

1980s: For external and internal demarcation, ‘There is no such thing as society’

What does it create?

1920s: Silence, space and landscape of memory

1980s: Pride, order and the exclusion of outsiders

How does it work?

1920s: Like a mist or a scent

1980s: Like a fence or a boundary marker

What threatens it?

1920s: The loss of harmony

1980s: The loss of control

Perhaps the differences between the two types of cultural memory become clearer when they are compared. The 1920s portray Midsomer County on the surface, while the 1980s reveal what lies beneath. This is no coincidence. By the 1980s, cultural memory was no longer about mending, but about sorting; it attempted to impose coherence on a past that was falling apart. Thatcherism weaponised nostalgia. The idealised cultural memories of the interwar period and the 1950s as its carbon copy became an ideology. This was no longer merely a longing for the past; it was a demand that the past should rule the future.

When Thatcher’s tenure was almost over and the consequences of her policies were becoming apparent, Graham’s first Barnaby novel, ‘The Killings at Badger’s Drift’, was published. It is not just a crime novel; it is also a subtle autopsy of English society at the end of the 1980s, through allegory and caricature as the scalpels.

Rather than expressing her criticism of Thatcherism openly, clearly, programmatically or polemically, Caroline Graham incorporates it structurally and through the characters. John Nettles once said that Graham’s novels were ‘a comedic take on the whodunit, in the glorious English tradition of the detective story, stretching back to Conan Doyle and before. It is almost, but not quite, a send-up.’

The Barnaby novels and the TV episodes based on them essentially follow a pattern that transcends the classic whodunnit.

Initially, everything seems idyllic. However, underlying tensions – what DCI Barnaby uttered in ‘Dead Man’s Eleven’ (S02E03): ‘Every time I go into any Midsomer village, it’s always the same thing: blackmail, sexual deviancy, suicide, and murder’ – are always present. Inevitably, one or more murders occur, acting as a catalyst for the ‘purification’ of paradise – in this case, Midsomer as a personification of England. These murders briefly destroy the idyll, providing a stark contrast to the paradisiacal one that existed on the surface.

Guided by the detectives, we navigate this purgatory in an attempt to restore the idealised memory of England, separating the wheat from the chaff. This is difficult because everyone is somewhat suspicious, and there are both good clues and false leads.

Resolving the case restores justice and a sense of safety, spreading a feeling of comfort and well-being. It’s not merely a happy ending, but a cosy one. However, the events and characters and their connections to each other convey Caroline Graham’s criticism of Thatcherism: honour and status can lead to murder, and tradition can serve as a moral backdrop. The village community is not purely supportive; it is full of hidden class contempt, ambition, and selfishness. The establishment does not protect the weak, it protects deception. Bourgeois moralism dressed up as personal responsibility merely covers up ruthlessness and selfishness.

As Daniel Casey, who played Sergeant Troy in the TV adaptation and DCI Tom Barnaby in the stage adaptation, so aptly said in a 2025 interview with BBC Breakfast: ‘The characters in Midsomer Murders have always been larger than life.’ This is spot on: the characters are not merely bizarre, eccentric or exaggerated; they are condensed allegories, just as the Midsomer backdrop is itself an allegory for the idealised English landscape. The characters also take on a certain personification. They can be described succinctly as ‘the miser’, ‘the nostalgic’, ‘the progress fanatic’, or, in the case of Midsomer, they can also convey criticism of Thatcher. Examples include Max Jennings’ selfishness and betrayal of Gerald Hadleigh in ‘Written in Blood’ (S01E01) or Harold Winstanley’s cover-ups in ‘Death of a Hollow Man’ (S01E02). Not to mention Iris and Dennis Rainbird in ‘The Killings at Badger’s Drift’.

Let us focus on with Iris and Dennis Rainbird, who embody the classic couple for othering and eccentricity in ‘The Killings at Badger’s Drift’. Morally depraved and unscrupulous, they are ultimately victims rather than the murderers. The two characters are shrouded in mystery because they have family roots in Badger’s Drift and its community: Iris was born there and was taught by Emily Simpson at the parish school. Despite their roots, however, they do not belong there. They stand out in Midsomer County through their behaviour and clothing, but in a different way to people socialised in London and its suburbs. Rather than fitting in, they undermine the community spirit on several levels and ride roughshod over it.

Take their home, for example: outside, it is a bungalow rather than a cosy English cottage, and inside, the furnishings, rituals and artfully arranged tea accoutrements attempt to position the Rainbirds as upper-middle-class. The Rainbirds are just as bizarre as their home. But it’s not just their lifestyle or Dennis’s Porsche. Their neighbourhood watch would have delighted Thatcher, but that’s not all: this ‘watch’ is also their informal blackmail economy – sustaining their supposedly upper-middle-class lifestyle. They blackmail other members of their community for their misdemeanours.

The novels crystallise the social and cultural aftershocks of Margaret Thatcher’s England and its underlying consequences, albeit without naming them directly. The humour, caricatures and allegories articulate what explicit commentary could not. A disarmingly devastating piece of subtextual mastery. The villages thus become anachronisms and historical monuments, serving as memorials and microcosms of idealised village communities.

So, what is the conclusion? And what does Midsomer mean today? Why does it touch people far beyond England?

Epilogue: Midsomer Today

Midsomer Murders is quintessentially English. This has never been questioned. It conveys a timeless image of England’s rural idyll and cultural heritage, with an impact not only in England, but worldwide. Essentially, it reinforces the desire to escape the stresses of everyday life and immerse oneself in a landscape perceived as timelessly unspoilt. This is not very different from a hundred years ago, when city dwellers travelled to the countryside to rest their minds. This is not because the countryside is rural, but because the nostalgic atmosphere of cultural memory makes it seem untouched by the spirit of the times – past, present and future collapse into one another.

This is the secret to all heritage tourism: it’s not about the space or the time, but the atmosphere. It is a nostalgic setting and storytelling that evoke the memories and longings of those who come. This is also the secret to the success of Midsomer Murders and many other British series worldwide. It’s not just that it’s an English landscape; the English landscape evokes nostalgia and an atmosphere that people around the world long for.

In Our Island Stories, historian Corinne Fowler has described this imaginative geography with precision: In the ‘national imagination’, the countryside became a ‘place of idyllic seclusion and retreat from urban life’, ‘a place of almost prelapsarian innocence’, ‘steadfast and reassuring’, believed to have ‘existed since time immemorial’ and ‘attached to ideas of nationhood as though by an umbilical cord’.9

Midsomer Murders borrows directly from this idealised vision of the countryside – the eternal village that defines a nation.

The setting matters because it represents more than just scenery.

The atmosphere of Midsomer Murders is England itself, in miniature.

Thank you!

If you enjoyed this essay and would like to support my work on British cultural history, you can support me on Ko-fi (it’s like Buy me a coffee). Your support allows me to spend more time researching and writing deep dives like this one.

Further Readings

Caroline Arscott, ‘Victorian development and images of the past’, in The imagined past. History and Nostalgia, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester University Press, 1989), pp. 47-67.

Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw, ‘The dimensions of nostalgia’, in The imagined past. History and Nostalgia, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester University Press, 1989), pp. 1-17.

Malcolm Chase, ‘This is no claptrap, this is our heritage’, in The imagined past. History and Nostalgia, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester University Press, 1989), pp. 128-46.

Andy Croft, ‘Forward to the 1930s. The literary politics of anamnesis’, in The imagined past. History and Nostalgia, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester University Press, 1989), pp. 147-70.

Nicholas Dames, Amnesiac Selves. Nostalgia, Forgetting, and British Fiction 1810-1880 (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Fred Davis, Yearning for Yesterday. A Sociology of Nostalgia (The Free Press, 1979).

Corinne Fowler, Our Island Stories (Penguin, 2025).

Peter Fritzsche, ‘Specters of history. On Nostalgia, Exile, and Modernity’, in The American Historical Review 106.5 (2001), pp. 1587-1618.

Peter Fritzsche, ‘How Nostalgia Narrates Modernity’, in The Work of Memory. New Directions in the Study of German Society and Culture, ed. by Alon Confino and Peter Fritzsche (University of Illinois Press, 2002), pp. 62-81.

Patrick H. Hutton, ‘Reconsiderations of the Idea of Nostalgia in Contemporary Historical Writing’, in Historical Reflections 39.3 (2013), pp. 1-9. doi.org/10.3167/hrrh.2013.390301.

Stephen Kohl, ‘Rural England in Moderne und Zwischenkriegszeit. Zur Nachgeschichte eines literarischen Konstrukts’, in Poetica 27.3/4 (1995), pp. 374-95, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43028078 (accessed 23 December 2025).

David Lowenthal, ‘Nostalgia tells it like it wasn’t’, in The imagined past. History and Nostalgia, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester University Press, 1989), pp. 18-32.

David Matless, Landscape and Englishness, 2nd edn, (Reaktion Books, 2016, Kindle edn).

Howard Malchow, ‘Nostalgia, “Heritage”, and the London Antiques Trade: Selling the Past in Thatcher’s England’, in Singular Continuities. Traditional, nostalgia, and identity in modern British culture, ed. by Georg K. Behlmer (Stanford University Press, 2000), pp. 196-215.

Marcel Proust: Swann’s Way (Modern Library, 1956).

Constantine Sedikides and Tim Wildschut, ‘The sociality of personal and collective nostalgia’, in European Review of Social Psychology 30.1 (2019). pp. 123-73.

Tim Wildschut et al, ‘Nostalgia and Populism. An Empirical Psychological Perspective’’ in Zeithistorische Forschungen 18.1 (2021). URL: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/75729(accessed 23 December 2025).

Janelle Lynn Wilson, ‘Here and Now, There and Then. Nostalgia as a Time and Space Phenomenon’, in Symbolic Interaction 38.4 (2015), pp. 478-92, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/symbinte.38.4.478(accessed 23 December 2025).

Eric G. E. Zuelow, A History of Modern Tourism (Red Globe Press, 2016).

Notes

- Janelle Lynn Wilson, ‘Here and Now, There and Then. Nostalgia as a Time and Space Phenomenon’, in Symbolic Interaction 38.4 (2015), pp. 478-92. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/symbinte.38.4.478; Tim Wildschut, Constantine Sedikides and Anouk Smeekes, ‘Nostalgia and Populism. An Empirical Psychological Perspective’, in Zeithistorische Forschungen 18.1 (2021). DOI: 10.14765/zzf.dok-2297; Constantine Sedikides and Tim Wildschut, ‘The sociality of personal and collective nostalgia’, in European Review of Social Psychology 30.1 (2019). pp. 123-73; David Lowenthal, ‘Nostalgia tells it like it wasn’t’, in The imagined past. History and Nostalgia, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester University Press, 1989), pp. 18-32.

- Marcel Proust: Swann’s Way (Modern Library, 1956), pp. 61-62.

- Peter Fritzsche, ‘Specters of history. On Nostalgia, Exile, and Modernity’, in The American Historical Review 106.5 (2001), pp. 1587-1618 (pp. 1589-1591, 1611); Peter Fritzsche, ‘How Nostalgia Narrates Modernity’, in The Work of Memory. New Directions in the Study of German Society and Culture, ed. by Alon Confino and Peter Fritzsche (University of Illinois Press, 2002), pp. 62-81 (p. 79); Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw, ‘The dimensions of nostalgia’, in The imagined past. History and Nostalgia, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester University Press, 1989), pp. 1-17 (pp. 2-7); Fred Davis, Yearning for Yesterday. A Sociology of Nostalgia (The Free Press, 1979), pp. 49-50, 116; Patrick H. Hutton, ‘Reconsiderations of the Idea of Nostalgia in Contemporary Historical Writing’, in Historical Reflections 39.3 (2013). doi.org/10.3167/hrrh.2013.390301.

- Nicholas Dames, Amnesiac Selves. Nostalgia, Forgetting, and British Fiction 1810-1880 (Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 6.

- However, there is good reason to believe that Blake’s poem was a parody of the nationalistic fervour of the Napoleonic Wars, as he was a revolutionary and a radical who championed the poor and oppressed, not a nationalist. He was also anti-monarchy, anti-organised religion, anti-industrialisation and anti-establishment.

- Malcolm Chase, ‘This is no claptrap, this is our heritage’, in The imagined past. History and Nostalgia, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester University Press, 1989), pp. 128-46 (p. 128).

- David Matless, Landscape and Englishness, 2nd edn, (Reaktion Books, 2016, Kindle edn); Eric G. E. Zuelow, A History of Modern Tourism (Red Globe Press, 2016), p. 43; Stephen Kohl, ‘Rural England in Moderne und Zwischenkriegszeit. Zur Nachgeschichte eines literarischen Konstrukts’, in Poetica 27.3/4 (1995), pp. 374-95 (p. 381). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43028078.

- Lowenthal, Nostalgia tells, p. 30; Malchow, Nostalgia, Heritage, pp. 201, 206; Caroline Arscott, ‘Victorian development and images of the past’, in The imagined past. History and Nostalgia, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester University Press, 1989), pp. 47-67 (p. 47); Andy Croft, ‘Forward to the 1930s. The literary politics of anamnesis’, in The imagined past. History and Nostalgia, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester University Press, 1989), pp. 147-70 (pp. 154, 157, 169).

- Corinne Fowler, Our Island Stories (Penguin, 2025), p. xi.

1 thought on “Quintessentially English: The Atmosphere of Midsomer Murders”