•

(Caution: Contains spoilers for Episode: S05E03: Ring out your Dead)

Diesen Beitrag gibt es auch auf Deutschauch auf Deutsch.

•

Tom and Joyce Barnaby are sitting at the table in the kitchen, and Tom is looking through numerous papers, most of which are in front of him. In 1860, the vicar of Midsomer Wellow was thrown down a well and died. Before that, there had been real trouble with the local bell-ringers because he had tried to force them to attend services and had had their beer barrel removed from the ringing room. Although the case was obvious, the evidence was lacking and the witnesses remained silent.

Tom has Joyce look in the phone book to see if Ebbrell is still in Midsomer Wellow – nothing of the sort. Only towards the end of the episode does she find out: Her new friend Maisie Gooch, the local historian and church archivist at St Catherine’s, was born Ebbrell – and is the great-great-granddaughter of the murdered vicar. She vows revenge on the group that killed her ancestor.

The fact that the current bell-ringers of Midsomer Wellow are not related to the bell-ringers of 1860, and that some of their families did not even live in Midsomer Wellow in 1860, does not matter to her: the bell-ringers murdered her ancestor and brought misfortune upon the Ebbrell family, who have been living in poverty ever since.

So she takes vigilante justice into her own hands and kills the current bell-ringers to end what she sees as a curse. A very Old Testament way of thinking.

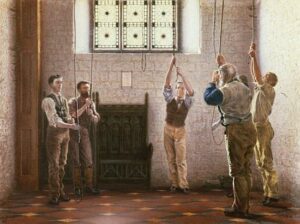

Bell ringing – loved and hated

Unlike many other countries, the UK has a tradition of ringing church bells by hand in a group. And it’s not done in any particular way, or in a constant cycle, but in a series of mathematical sequences that require an artistic and skilled performance. The activity can easily be described as a sport – a physical and mental job, because it also requires a great deal of concentration.

That’s why there are so many bell ringers in England – an estimated 40,000 in 2018, although the number fell sharply during the Covid 19 pandemic and the desperate search for new ringers for the coronation of King Charles III. All the church bells had to be rung by hand at the same time for the coronation.

This included the ringers of St Michael’s, Bray in Berkshire, where the episode was filmed. The ringing chamber was heavily modified for the filming, but also ‘restored’ to its original state at the expense of the production company. This entry tells the story. St Michael’s has eight bells, the tenor of which weighs a good ton. However, only the interior was filmed in Bray, the exterior was shot in Watlington, Oxfordshire, and the bells are from the church at Monks Risborough, Buckinghamshire.

Why not automatic?

The origins of bell ringing are thought to be relatively recent, dating from the 17th century. At that time, bell founders noticed that a special effect occurred when bells were swung in a particularly wide arc: the time between two strokes could be controlled by the clapper – and thus several bells could be rung in different sequences (“permutations”). This led to the development of full-circle ringing, in which a bell rotates 360° on its suspension on a headstock that was once made of wood but is now often made of steel.

Specially made ropes of flax (formerly Indian hemp) are attached to the bells and hang through holes in the ceiling into the ringing chamber. On these ropes there is a sally, a woollen handle woven into the rope to make the rope softer on the skin. With this rope, the ringers, standing in a circle as in the episode, bring their bell into the starting position: mouth up.

Two effects: Doppler & Decay

The sound of a manually struck bell is different from that of an automatically struck bell. The latter do not make a full circle and often have a counterbalance that controls the speed but not the sound effect of the double strike.

Let’s stay with the beginning described: The ringer is ready and has set his bell in motion until it stops with the mouth pointing upwards. If he now pulls on the rope, the bell accelerates downwards with up to three times its static weight. The clapper, made of wood, iron or steel, is pressed against the inner wall of the bell by the acceleration. At the same time, the rope from the wheel wraps around the bell, allowing the ringer to grab and pull the clapper, giving the bell the energy to swing back up with its mouth. The clapper is no longer pressed against the inner wall, but hits the wall on the opposite side. During the sound, the bell remains in motion, creating the Doppler effect. And as soon as the mouth of the bell is on its way down again, the clapper presses against the bell again, spreading the vibrations and reducing the intensity of the sound.

This means that you can have quick successions of beats – about two seconds – but they will not sound (much) alike.

Changing the sound

Due to the heavy weight of the bells, they cannot be stopped and must be struck once. However, it is possible to change the sequence of the bells by controlling the speed of the bells or by not making a full circle. This is how change ringing came about – a pre-determined set of bells struck in a controlled way, in order, in pre-determined sequences (‘changes’). They begin and end with rounds, which means that the bells are played according to their weight, starting with tremolo, the lightest.

No wonder they say it takes about six weeks to learn how to ring a bell, but at least a decade to become really good. And then there is the ringing with call changes, where one person, the conductor, indicates aloud when which bell is to be rung. In the episode, conductor Peter Fogden occasionally shows off during rehearsals, but is reprimanded for doing so because he knows the order by heart – this is called method ringing.

‘Go, Grandsire Double’

In Bray, as I said, there are eight bells, which makes 40,320 permutations. To play them all (‘full peal’) would take several hours. (With six bells it is ‘only’ 720 permutations and takes about half an hour).

Grandsire is the oldest method of pealing. It is rung according to a series of mathematical permutations and can only be extended to any number of odd bells in change.

The order of change ringing is quite simple to explain, as there is always a variation. After the rounds, the tremble remains in first place, then the second lightest bell and the tremble goes into second place, then third.

In this episode, conductor Peter Fogden tries to ring a Grandsire double in the rehearsal at the beginning of the episode, presumably as part of the audition for the competition. It may even be heard in the opening or closing sequence of the bell ringers’ contribution to Midsomer Wellow. (Hints welcome. No one has yet been able to answer this question for me.) Grandsire Double doesn’t make much of a difference, it just means that after the round each bell is rung twice in the first place:

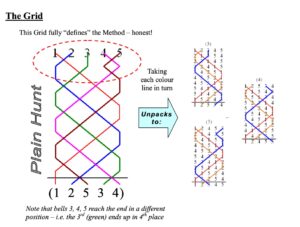

This is the simple hunt in Grandsire Double, as shown in Alistair Donaldson’s easy-to-understand diagram:

12345

21354

23145

32415

34251

43521

45312

54132

51423

15243

12534.

Only… Grandsire Double is played with five bells, but six bells are used in competition. How can this be? Well, in this case the biggest and heaviest bell, the tenor, is always played in the last position in the pattern.

So it starts with 123456, goes on to 213546 – 231456 – … and finally ends with 125346.

Read more about Midsomer Murders & History

The Chronology of Midsomer County by Year or by Episodes

Deep Dives into Midsomer & History

This is an independent, non-commercial project. I am not connected to Bentley Productions, ITV or the actors.

Literature & Further readings

- NN: How to interpret the Method Diagrams?

- Report by John Harrison on the filming of this Midsomer Murders episode in Bray: Murder in the belfry (Autumn 2001).

First published on MidsomerMurdersHistory.org on 29 February 2024.

Updated on 22 August 2025.

4 thoughts on “The Bell Ringers from Midsomer Wellow”